Ideas on the darker side of human beings

Merging findings from academic science and real-world art. Together, they shine an interesting light on human behaviour.

Context

When psychology is applied, it's often aimed at relieving mental distress. But first and foremost psychology is an experimental science (1). Since it's inception in 19th century Germany, it has been interested in staging experiments that inform us about human beings, and their internal worlds.

Marina Abramovic is a performance artist born in post-war Serbia (2). Together with the audience, her artwork explores universal human emotions that are sometimes inaccessible - even undesirable. In her work, shame, suffering, and mortality are often invoked.

Scientific experiments suffer from ecological validity (3). That is, they take place in a lab rather than the real-world. Because of this, psychological experiments take a sample of what might happen in the real world, they do not study the real world itself.

Performance art suffers from lack of experimental design. In the performances of Abramovic, it is impossible to control for conditions in the same way that an experiment could. For this reason, it may be harder to draw conclusions about exactly what happened in a performance, and why.

In other words, both psychology and the performance art have their unique limitations. Let's put them together and see what emerges. First, psychology. Then, art.

Classical psychological experiments

Following the two world wars, and the terrible atrocities that took place during them, academics asked questions like:

How could this happen? What effects do group dynamics have on people? And, what made people do the things they did?

Findings from classical psychology experiments are reported here.

First, the Asch experiments (4). Asch found that if you have a group of people and ask an individual within that group to answer a simple question (where the answer is obvious), that individual can be highly influenced by what the group says (even if the group offers an obviously incorrect answer).

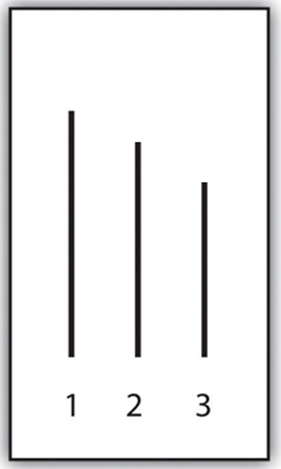

For example, in a lab environment, people were asked to look across the room to a picture of lines. These lines were clearly different lengths. And then the experimenter would ask: "which line is the shortest"? Crucially, everyone in the experiment was working in collaboration with the people who designed the experiment, expect one person, who wasn't aware that everyone else was in on the act.

So, one person is isolated and asked: which is the shortest line? Then, when they provide the correct answer, everyone else in the group disagrees. The group says: that line isn't the shortest, but it's the line on the left (which is clearly longer).

What tends to happen?

Around a third of people discount what they see and go with the group. Their ability to give the correct answer is swayed by what others think, even when the answer is obvious for them to detect. In this case a simple visual task: deciding the length of a line.

Why conform?

When asked why they gave the incorrect answer after the experiment ended, people said that they either conformed because they were scared of being ridiculed by the group, or they genuinely believed the group were correct, and they were wrong. Put differently, in this experiment, people conformed to others either to fit in or because they doubted themselves. Interestingly, autistic people do not conform to the group so easily (5).

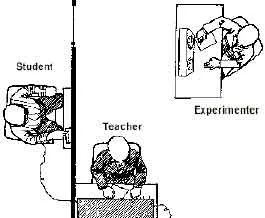

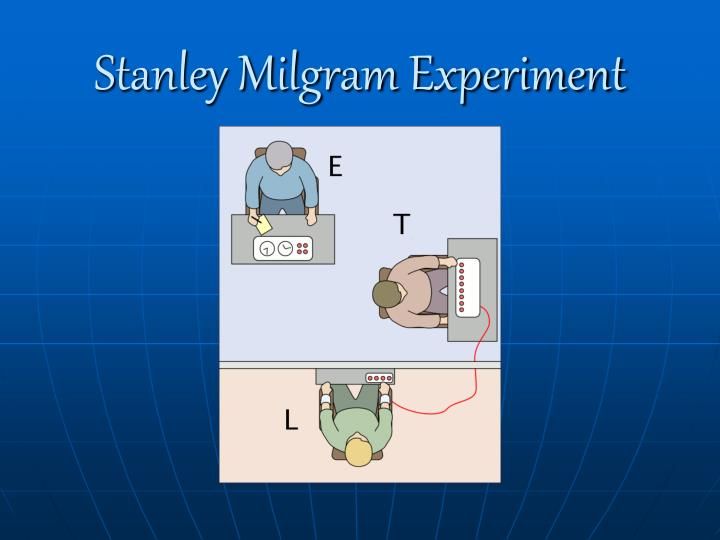

Second, the Milgram experiments (6). These studies focused on how the role of an authority figure influences the behaviour of others, especially when the authority figure encourages a person to inflict pain on another (again inspired by the atrocities of war).

People were invited to take part in a "learning study", and were put into pairs of learner and teacher. Then, the learner (actually a paid actor working in collaboration with the experimenter) goes to a room next door, is connected to an electro-shock machine, and must answer questions. Meanwhile the teacher (the person recruited for the experiment and who doesn't know what's going on) is inside another room with the experimenter, who tells him to shock the learner each time they make a mistake. Note that the shocks were not real, but the acting learner made them sound and feel real.

The experiment simply asked: how much pain is an ordinary citizen willing to inflict on another ordinary citizen?

As we've said, the person inflicting the electro-shock damage, the teacher, must increase the voltage each time the learner gets a question wrong. There were 30 switches on the shock generator marked from 15 volts (slight shock) to 450 (danger – severe shock).

And finally, the experimenter plays the role of the authority figure, who encourages the teacher to administer the shocks - even if the teacher does not want to, and the learner (who is an actor) cries out in pain, which of course he does.

To encourage the teacher to shock the learner when he objects, four prods were used:

First prod: "Please continue".

Second prod: "The experiment requires you to continue".

Third prod: "It is absolutely essential that you continue".

Fourth prod: "You have no other choice but to continue".

The findings from the original 1963 study?

Two-thirds of people recruited to play the teacher role shocked people to the highest level. Again, the highest level was marked 450 volts (danger - severe shock). What is more, the person getting shocked cried out in pain, asking for the experiment to be stopped. But the authority figure prodded, and people upped the ante all the way to severe shock.

So there's experimental evidence that people can be swayed by others rather easily. And that everyday people can inflict severe pain on their fellow citizens when pressured by authority. Now we turn to an intrepid artist who took these tentative findings a step further.

The Art of Marina Abramovic

It was the 1970s. Like many young people, Marina Abramovic was finding her way in life, and in her work. Painting, she decided, wasn't for her. Instead, she wanted her artwork to be engaging, visceral, and grounded in experience (2).

What is art? Not something separated from life, she decided, but art was a part of life. The child of two communist soldiers in the second world war, her home life was militaristic: violent, repressive, and excessively orderly. In particular, her mother rigorously enforced a "home by 10pm curfew", which she basically obeyed until she left home - at age 29.

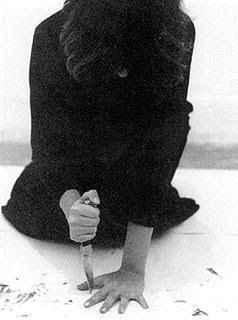

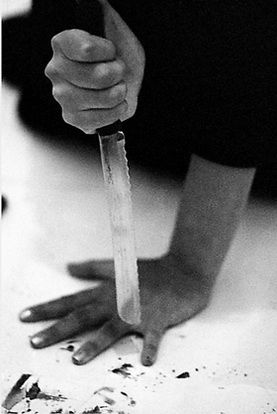

She found freedom through performance. That is, high-risk, vulnerable, and bodily performance. Imagine sitting in front of an audience and placing your hand on white paper. Then, you pick up a knife and stab between your fingers at speed, the white paper recording any cut or blood.

For most people, this would not be appealing - even stupid and dangerous. But for young Abramovic it was exhilarating, empowering, and freeing. It was her first major artistic performance - Rhythm 10, she called it. It would evolve into a series of performances that focused on themes of the human body, pushing it's limits, and finding personal freedom in the process. After Rhythm 10, and feeling the wild applause from the audience, she writes:

"I had experienced absolute freedom - I had felt that my body was without boundaries, limitless; that pain didn't matter, that nothing mattered at all - and it intoxicated me... No painting, no object that I could ever make, could ever give me that kind of feeling, and it was a feeling I knew I would have to seek out again and again and again..." (2).

And so, age 27 and with blood-stained hands, she planned to create more art. To many back then - especially to her mother - what she was doing was bizarre; ridiculous, not artistic. Of course today, 50 years later, she is considered one the best performance artists in the world (7).

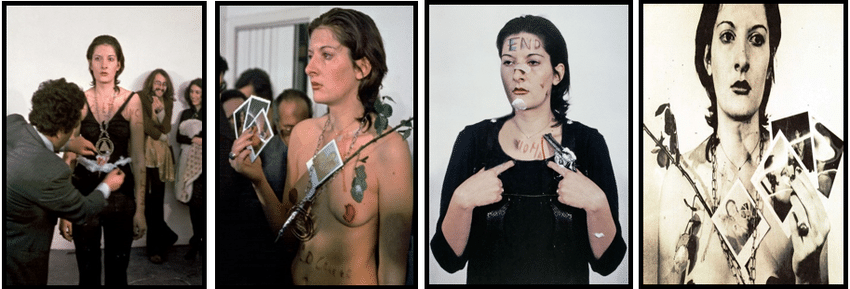

A year later Marina performed Rhythm 0, probably her most ridiculous, brave, and notorious work. It's the kind of work that, for ethical reasons, experimental psychology could never produce. Yet what it produced was incredibly valuable psychological data.

At a gallery in Naples, she laid 72 objects on a table. Then, the audience were informed that for the entire 6 hour long performance, they could use these objects on the artist as they wished. More than this, the artist would remain passive throughout the show, and accepted full responsibility for the consequences of the performance.

The performance information read:

"I am the object... use the objects on me as desired... I take full responsibility" (2).

Here was a test: the limits between performer and audience. Some objects could cause pleasure; others, pain. What were the objects?

Some examples:

Honey, oil, scarf, hat, apple, box of razor blades, hammer, saw, gun, and a single bullet.

What ensued was a strange but deep lesson in human psychology.

Rhythm 0

For the first 3 hours things were relatively tame, so the story goes (8). People touched her, drew on her, and in general were nervous, playful.

As the evening went on things took a sexual turn, something the audience - not the artist - chose. The scissors were used to cut her clothes, exposing her breasts. She was carried around and laid on the table. Someone used a razor to cut her neck, causing a scar she still has today, and then sucked her blood. And an art critic present later commented on how members of the audience sexually assaulted her. At the climax, a small man stood near her - and breathed heavily.

Out of everyone in the audience that night, she later wrote, it was that small man who scared her the most (2). He picked up the gun, loaded it, pointed it to her neck, and began wrapping the passive artist's fingers around the trigger. At this point some audience members felt that he had gone too far, a fight broke out, and he was thrown out of the gallery. At some point during the performance, female audience members wiped the tears from the young artists eyes.

Without question, her clout in the art world today exists partly because of her commitment to performance. Indeed, throughout the night and despite what was happening to her, she committed to her 6 hour performance, remaining passive and accepting the consequences - just as she promised.

In a final twist at 2am - when the performance ended - she became active again, announcing to the audience that the show was over, and stepped towards them. And how did they react? They ran! Unable to face her and presumably ashamed of their actions or scared about how she might retaliate, most audience members avoided her, much like an internet troll who is meeting their target in real-life for the first time, or a child caught doing something they know to be wrong.

Reflecting on this night many years later, she admitted that:

"the experience I drew from this work was that in your own performances you can go very far, but if you leave decisions to the public, you can be killed" (2).

In this performance she'd gone too far, and would never repeat again something like this. To varying degrees, she was traumatised: physically and psychologically. It was the presence of the men's wives that evening, she later noted, that probably prevented her from being raped. Crazy as she was on that night in Naples to expose herself to others so frankly, I think Marina Abramovic performed one of the most powerful artistic works of human beings that I'm currently aware of.

Ridiculous? Maybe. Pure genius? Almost definitely.

Art and science; science and art

Art and science are not in conflict. Both are creative; both aim to explore unexplored territory; both produce work that encourages us to look at the same world in a different way.

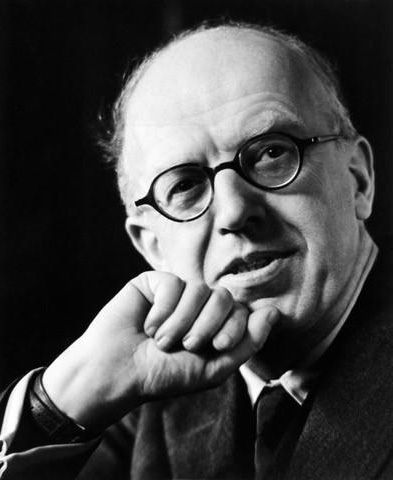

A famous lecture was once delivered at the University of Cambridge by the physicist turned novel writer, C. P. Snow (9). In it he made the case that there needs to be more co-operation between art and science. Too often had he been hanging around book people who knew little about basic science, and vice versa. Without this bridge of knowledge, Snow commented, people just discount the value of the other, assuming their expertise to be the most important, and are prone to spread false information about alternative viewpoints they know little about.

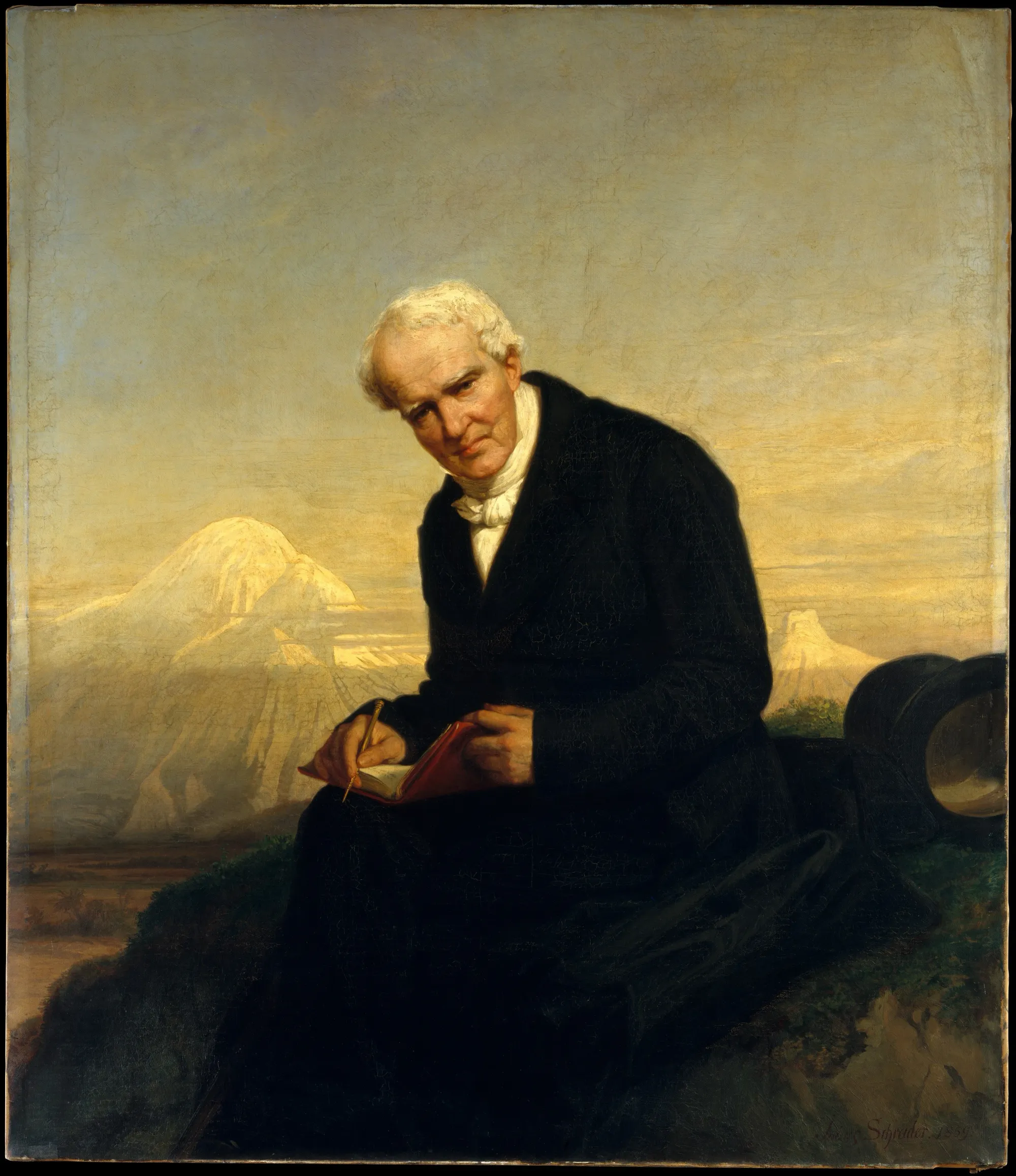

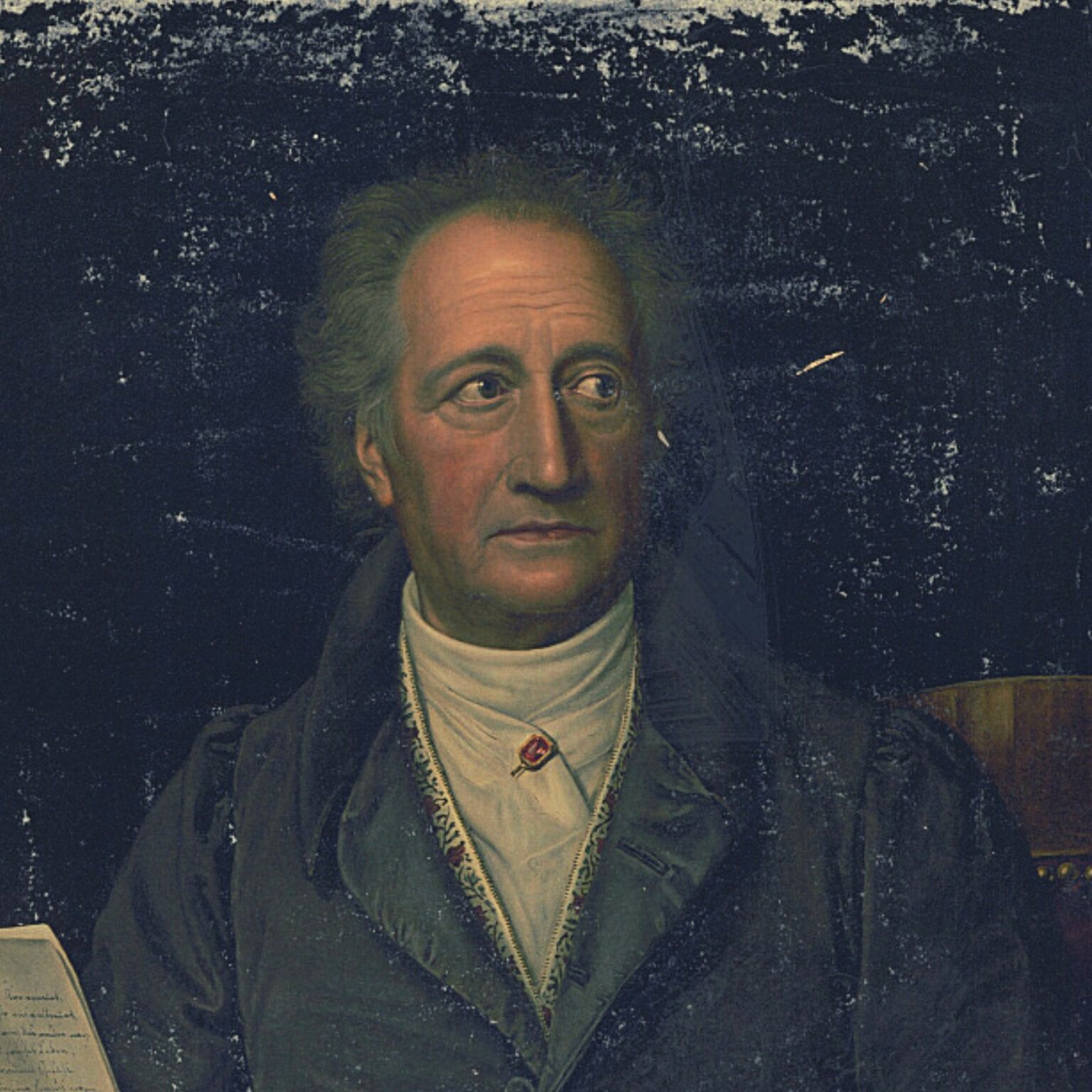

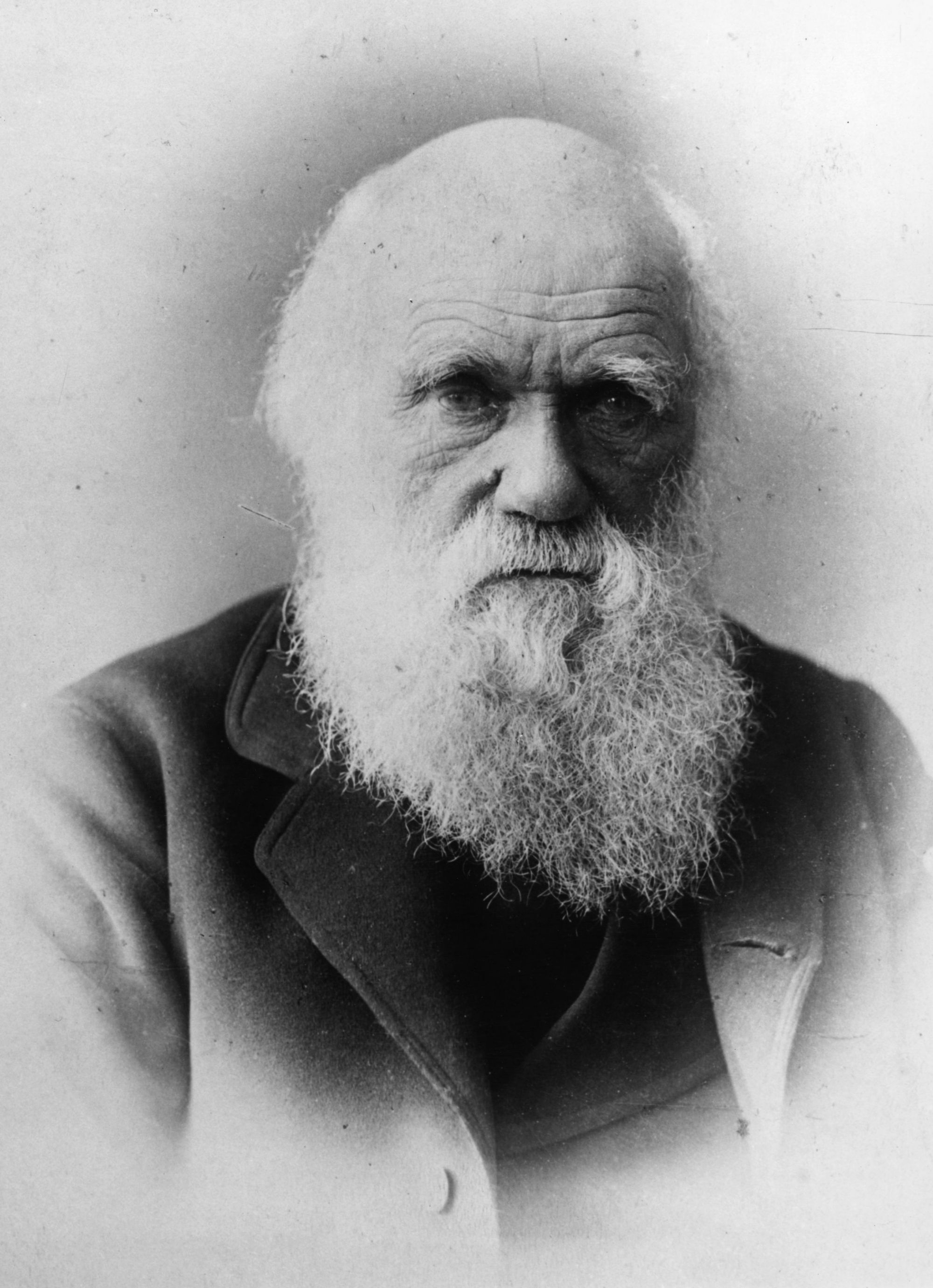

The great Prussian scientist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt was a great advocate of art and science (10). He wrote about science artistically, including technical detail alongside raw emotion. Inspired by the poet and scientist Goethe, Humboldt's colourful life would later inspire the decision of young Charles Darwin to sail around the world, an event which was crucial for developing his famous theory: evolution by natural selection.

In some sense, scientists and artists are probably inspired by the same instinctual forces (11). Attention to detail, divergent thinking, and a desire to understand the world are critical in both pursuits. Here science and art have given us a slice of the picture about humans, and how they can be.

Strict experiments showed how people can be influenced by others when the task is simple, and that people are prone to following orders for far too long. Artistic performance showed how when people are given complete freedom with no punishment, they are prone to abuse it. I'm interested in the implications of what these events can teach us.

In life there are times to listen to others and times to go with your gut feeling, even if it means going against the crowd. There are times to follow orders and times to stand up for what you believe is right, even if you risk confrontation. There are times to let others take the lead and there are times when you must step in to take the course of events in another direction, even if it means feeling stupid.

Knowing which path to take and when is of critical importance; knowing which path to take and when, however, is not at all straightforward. These are central tensions in life - for all of us. Maybe the science and art presented here teaches us about ourselves. After all, they just describe what people did, and I'm a person too.

Ignoring a gut feeling at the wrong time may allow others to sway your decision in completely the wrong direction, and into a bad relationship, or maybe by being unable to get out of one. Following orders without thinking can lead to anything, and it is too easily done. And standing by when you should be standing up can lead to the psychological and physical trauma of a brilliant young artist making her way in the world.

I believe these scenarios presented teach us that it's very difficult to take appropriate action when the time calls, or the pressure builds. They're grim lessons for our human nature and our human culture. More than anything, they're art and science that's worth knowing about.

References

1) Hergenhahn's An introduction to the history of psychology (2013)

2) Abramovic's Walk through walls (2016)

3) Dancey and Reidy's Statistics without maths for psychology (2017)

4) Reported in McLeod's Simple Psychology blog, accessed at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/asch-conformity.html

Original paper's here:

Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgment. In H. Guetzkow (ed.) Groups, leadership and men. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press.

Asch, S. E. (1952). Group forces in the modification and distortion of judgments.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 70(9), 1-70.

5) Yafai AF, Verrier D, Reidy L. Social conformity and autism spectrum disorder: a child-friendly take on a classic study. Autism. 2014 Nov;18(8):1007-13. doi: 10.1177/1362361313508023

6) Reported in McLeod's Simple Psychology blog, accessed at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/milgram.html

Original papers here:

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 371-378.

Milgram, S. (1965). Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority. Human relations, 18(1), 57-76.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. Harpercollins.

7) Reported by Anthony Dexter Giannelli on Artland Magazine's website, accessed at: https://magazine.artland.com/performance-art-top-10-contemporary-artists/

Also reported by Jeff Koons in a Masterclass article, accessed at: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/performance-art-guide

8) Reported by Catherine Wood on Tate museum website, accessed at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/abramovic-rhythm-0-t14875

9) C. P. Snow's The Two Cultures (1959)

10) Andrea Wulf's The invention of nature (2016)

11) Peterson's Beyond Order (2021)