Kant's big idea

This post is an essay on the history of Immanuel Kant's big idea, how it relates to contemporary brain science, and some of its wider implications

I like the history of ideas.

Our ideas today - such as how brains work - are based on ideas that came before them, and so can be traced back.

Here, I'll tell the story of how an idea from a Prussian philosopher, Immanuel Kant, still informs how the brain sciences see the world, and consider some of its wider implications.

Specifically, implications concerning the more extreme versions of postmodern philosophy and about political discussion more generally.

A big note though. Obviously this not the philosophical roots for the entire science of brains! Rather, it's one aspect - one part of the story (the ideas could be traced back in multiple ways, and certainly further back than Kant's time).

Immanuel Kant was a Prussian philosopher who lived in the 18th and into the early 19th century. He lived in Konigsberg.

Interestingly (we'll begin with a quick detour), Konigsberg today is now part of Russia, called Kaliningrad, and it's a unique enclave in Europe.

See below:

You can imagine today that since the Russia's invasion of Ukraine, there's been problems with getting supplies and resources to Kant's former homeland, where Russian nationals still live (surrounded by Europe, who imposed all sorts of trade embargos on Russian territory).

Regardless, I am told that Kant's writings are immense.

He wrote about a universal morality, democracy, and perpetual peace (1).

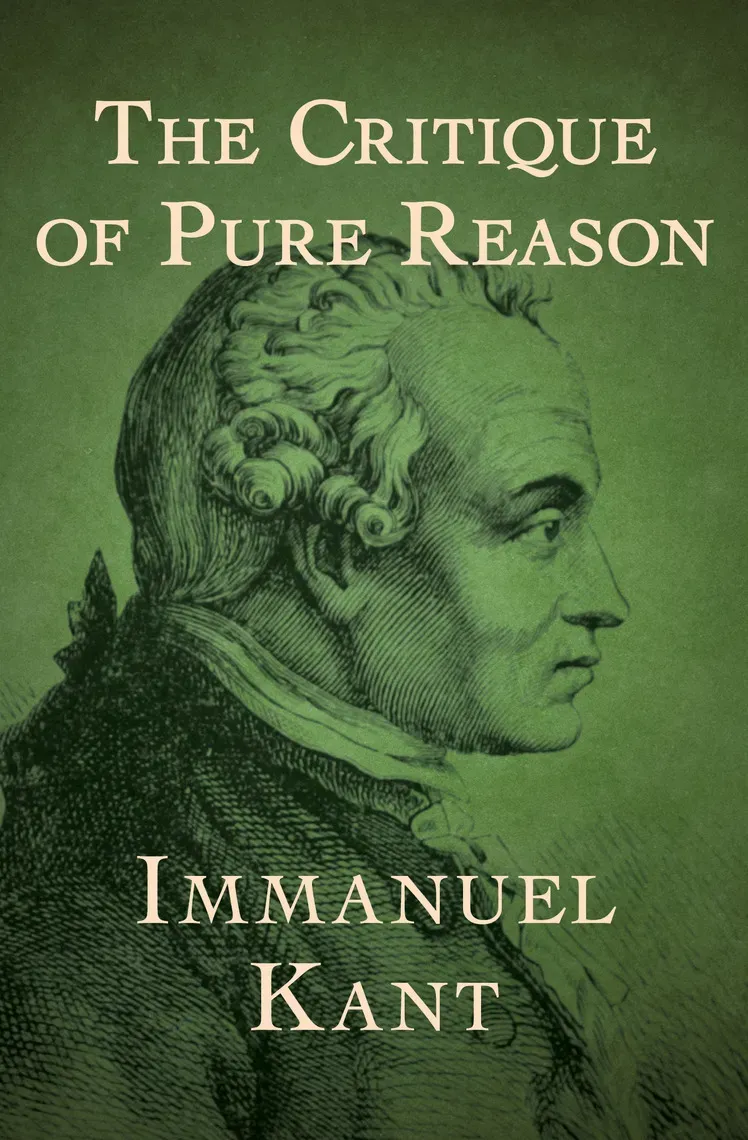

What we are interested in, however, is his argument in The Critique of Pure Reason (2).

This book (which I haven't read but intend to) was written in a time today called the Enlightenment. It was written when science was developing rapidly, was dismantling traditional values, systems, and practices (3).

For a thousand years, European civilisation had followed the Christian Scriptures, which told a particular story about the world and how old it was (4).

But discoveries in physics and geology were telling a different story: not only is the world probably much older than what the Scriptures told, but Earth was not even the centre of the universe.

At least in Europe, life had been organised according to principles that seemed to be wrong, quite wrong indeed.

And so the Enlightenment said:

"stop learning based on what has previously been written and instead devise new tests fit for new ideas, and, above all, embrace reason".

Or it said something like that.

Roughly speaking, that is the essence of the European Enlightenment (note that the Lebanese scholar Taleb considers the name "Enlightenment" patronising because many other cultures were Enlightened, too (5); the Arab world revived Aristotle's works, for example - though personally I think considering the scale of developments in Europe at that time, the name's cool, and a good fit).

In a world where fundamental truths (Scripture truths) had been overturned because of reason, what was to stop reason investigating, probing, and, if necessary, overturning everything?

But did reason have limits?

Are there places reason cannot reach?

This was the context in which Kant wrote his Critique, and his answer was yes: reason does have strong limits (2).

Kant dealt with a foundational problem: perception and reality.

What is perception?

And what is perception's relationship to reality?

Kant's central thesis was that when we perceive the world, we do not experience the world itself, but rather we experience our interpretation of it.

In other words, if I look at a table, I do not experience the table as it is, but I experience my interpretation of it.

Kant argued that, yes, human beings can use reason to understand the world and to get results - like in the industrial revolution where tangible results were real.

However, this process cannot overcome one severe limitation, the fact that reasoning brains are trapped inside skulls.

And because brains are trapped inside skulls, we do not experience the world directly, and therefore, strictly speaking, we can never know the world as it is.

For Kant, reasoning brains were interpretation-machines who could never come into contact with the world itself. Because of this fact, an institution such as religion was untouchable by reason, since deep questions, the ones that religions ask and answer, were out of reach for reason.

I'm told that one of Kant's motives for writing his legendary book was in essence to protect religion from reason, which was posing big questions to institutionalised Christianity.

Not long after Kant, a different philosopher would declare that "God is dead!", and today most students in the United Kingdom I've met aren't too bothered about Religious Education (6).

Though there is decent evidence that religious people today are happier and may be more likely to take part in community-based activities than secular folk, religion in the West today is diminished since Kant's days (7).

Interestingly, however, Kant's basic argument is generally accepted in scientific circles.

Again, I'm told (because I haven't read it directly) that a different influential philosopher - Sir Karl Popper - used to write that human brains were theory-laden (8).

That is, when humans create scientific ideas about the world, those theories themselves emerge from brains, which are biased in their particular ways.

Physics, chemistry, biology, and psychology cannot "break free" from their theory-laden brains. Humans have ideas, but they are not objective ideas about the world as it is.

Instead, these ideas (theory of evolution, relativity, chemical bonding etc.) have human bias built-in.

Because of this, it is so important for science to progress through transparent co-operation and competition (9). Scientists should test ideas against other ideas, and assume that everyone can be wrong because they are human.

Popper's theory-laden talk is an extension of Kant's basic message.

Today, all science progresses in the knowledge that theory-laden human brains cannot know the world directly, but instead know only their interpretation of it. Theories are often tested in the sense of asking a question: what is the probability that this result could be achieved in a world where there was no actual effect?

In other words, what is the probability that we could observe these patterns of results by strictly chance alone? Our conceptions are about minimising the role of randomness, rather than aiming for absolute accuracy.

Note that some scientific ideas are more than mere interpretations, however. Evolution explains how life on earth works, and the laws of physics seem to be true across the known universe (but more on this interpretation-realism debate later).

On the other hand, perhaps they do not hold true in the universe that we do not yet know.

All we know today is that the universe is massive, and things seem to work here in particular ways, but this may not hold true out-there...

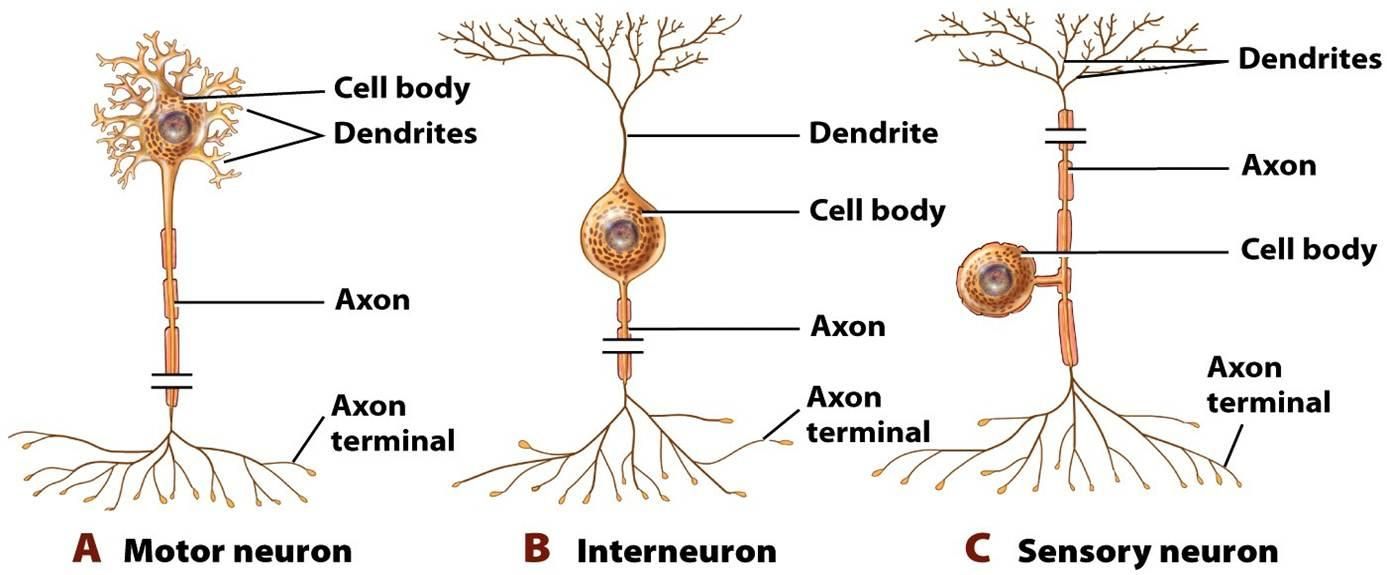

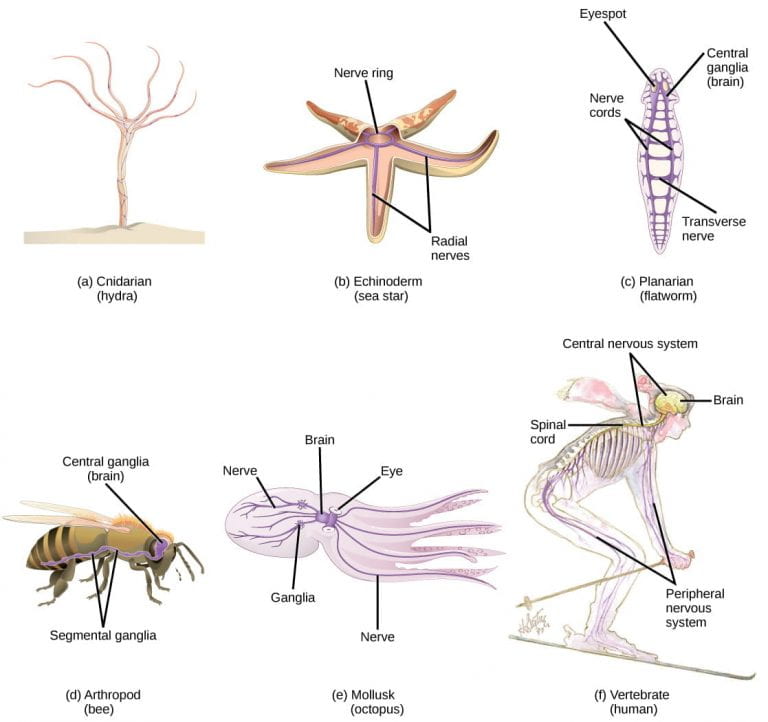

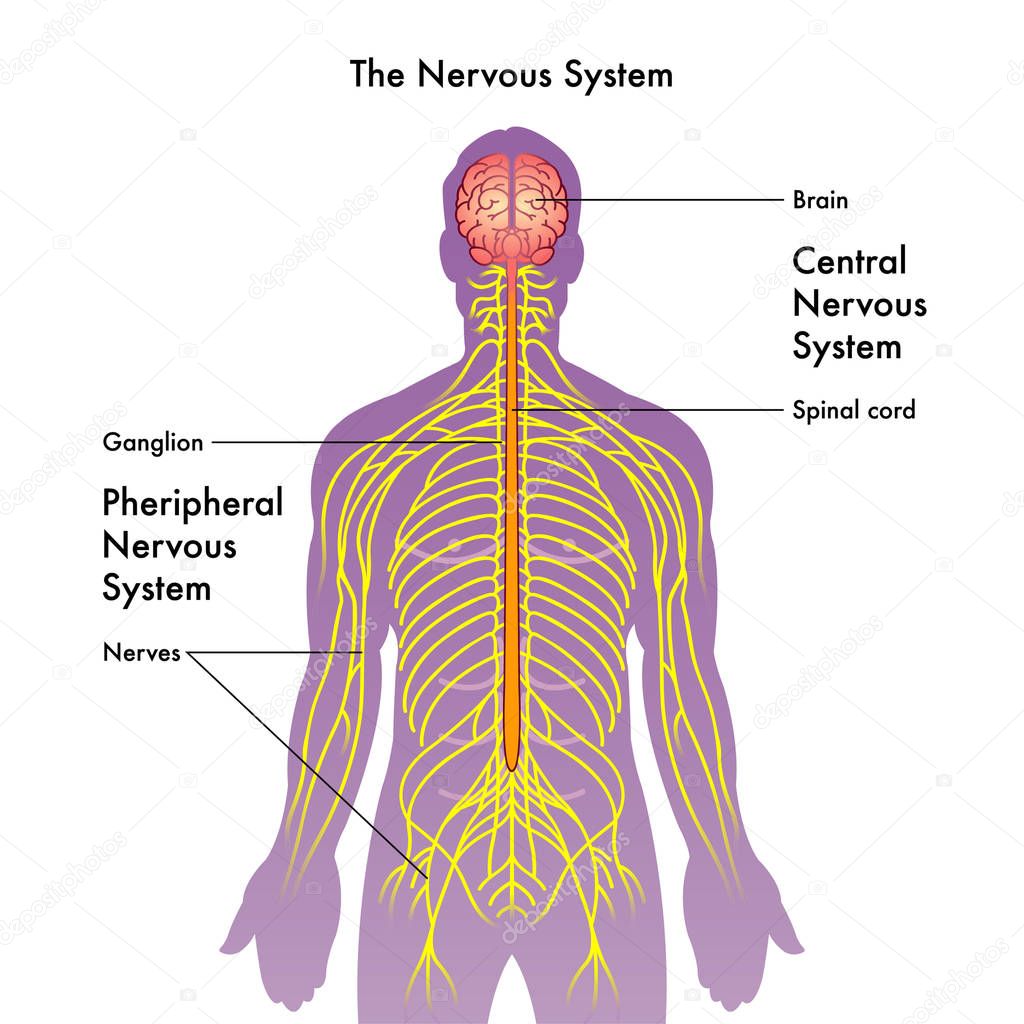

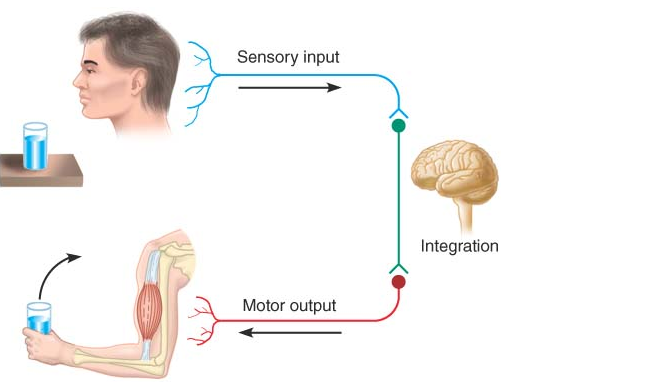

Getting more specific, both psychology and neuroscience have elaborated on Kant's argument. Any student of this subject will learn early on about nervous systems and neurons.

Neurons are small cells in the nervous system. They are the units that make up the nervous system, permitting information to be communicated across the brain and body.

The nervous system is the name for a combinatorial information processor that allows organisms to pick up and interpret information from the world.

We humans have very similar nervous systems to all other vertebrates, and because they are so similar, brain science students will often study the nervous systems of our fellow animals (10.) This is why most of scientific research is done on animals, like mice, rats, and fruit flies.

Having said this, neuroscience is recently undergoing a genuine revolution because of computer technologies which permit brain scans, whereas before we had to investigate brains after death, or make guesses like the Phrenologists (who looked at the shape of brains, and drew conclusions like: "she will be a philosopher", or, "he will cheat on his wife").

Without computers, modern neuroscience would not exist, a great example that illustrates how technology informs the possiblity to attain new knowledge.

See some brain cells are below:

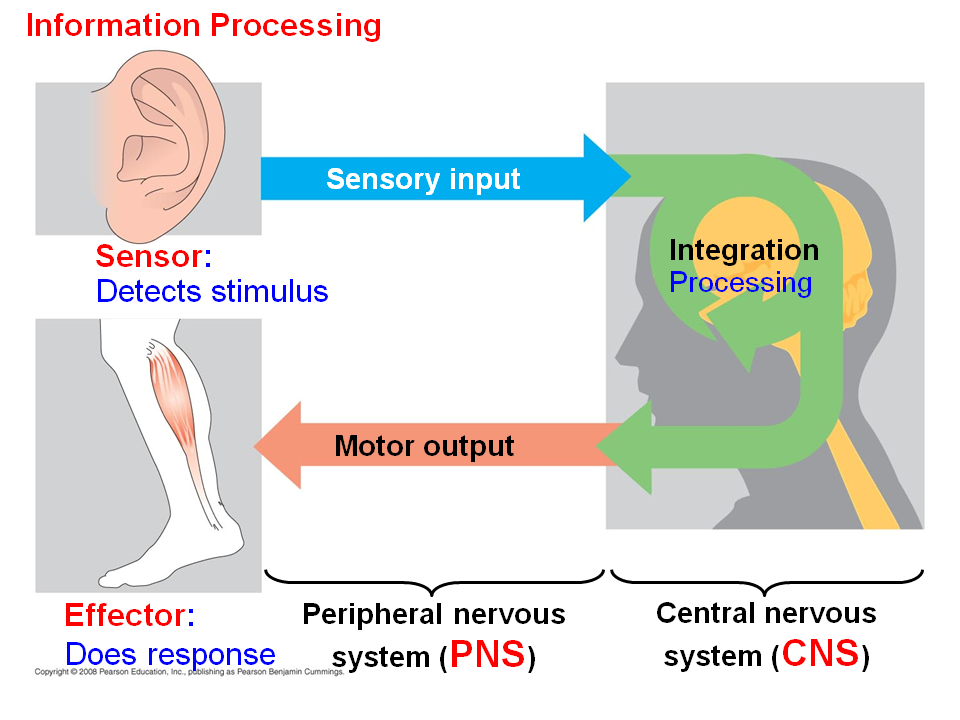

Knowledge of nervous systems can help to answer a question like: how does a person come to feel "touch"?

Well, first, a person touches the table with their finger.

This person's finger contains sensory neurons that detect the physical sensation, which then transmit this information into the brain, where the physical sensation gets converted into electrical energy (the language of the brain). Then, the brain processes this energy, and sends electrical signals via motor neurons to perform an action, such as:

"pick up glass from table!"

Notice how the language of the industrial revolution pervades the brain sciences, it's metaphorical power is considerable (metaphor and analogy about how things work are essential for scientific explanation, even discovery, 11).

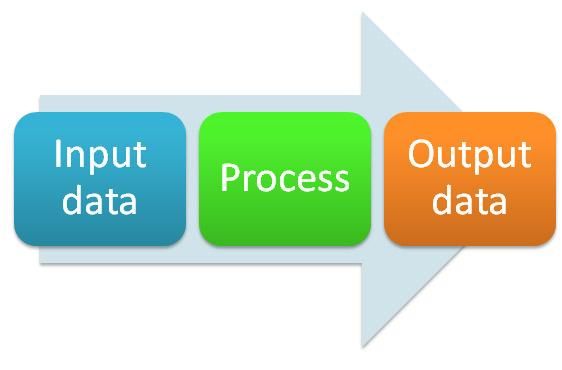

In essence, three words can explain how people feel sensations and move their arms:

- Input

- Process

- Output

Notice also that this solves the mind-body problem, which pondered how we could ever get from physical action from something non-physical (i.e., the mind).

The mind-body problem asked: where does the body end and the mind begin?

In our theory, known technically as the computational theory of mind, the mind-body problem is solved (12).

It gets solved because everything is physical.

Where does the body end and the mind begin? Well, "the body" doesn't really end... Nor does "the mind" really begin...

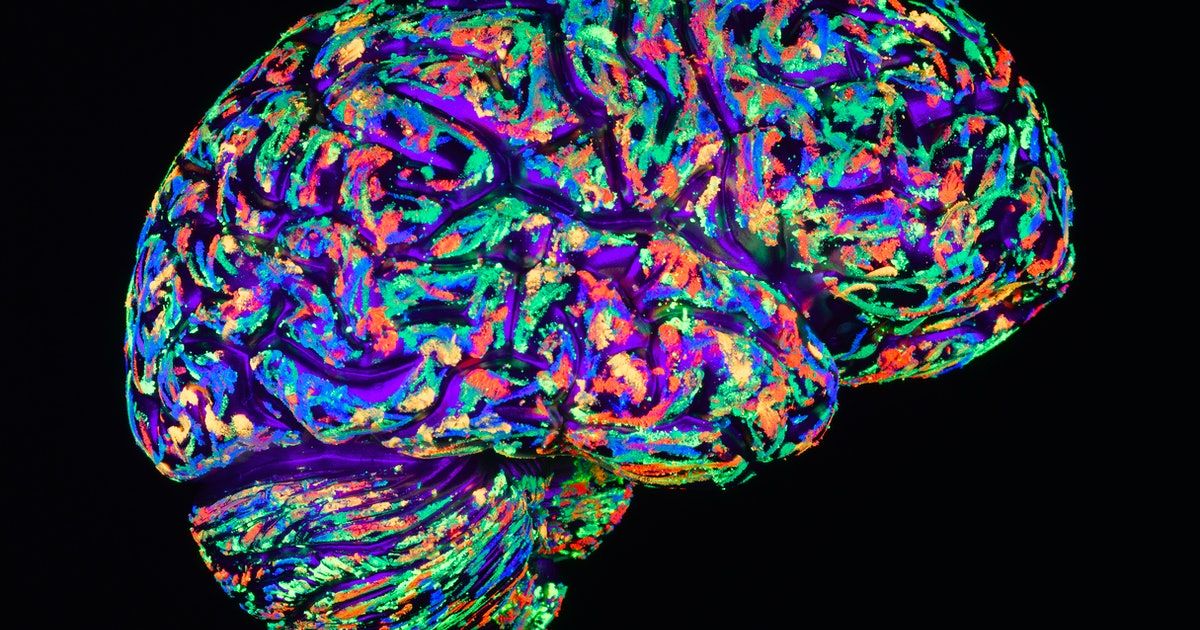

Consider the question: what is the difference between the brain and the mind?

According to contemporary brain science, there isn't one.

The mind is a description for brain activity, physical brain activity. The mind is what the brain does.

In other words, the mind doesn't exist - what exists are a ridiculous amount of physical neurons distributing information around brains and bodies.

The mind looks something like this below.

Beautiful, aren't they?

So, does the brain directly interact with the table?

No.

The brain interacts with particular information (converted electrical energy) that it receives from sensory neurons in the nervous system. Once it has received information in a way that it can understand, it can send signals in order to do something about the information.

In general, brain science students get taught that we do not perceive the world directly.

Instead, we perceive the world according to how our nervous system and brains work, which both seem to take in information in one medium, convert that information into something our brains can understand, who then send information back to our nervous system for action.

In other words, Kant was right.

Human beings (and their brains) are stuck inside themselves; they cannot know the world directly. Instead they know electrical energy, impulses, transmission, and interpretation.

If I am stuck inside my own brain, and you are stuck inside yours, where does that leave us?

One estimate today suggests that there are 7.98 billion people who live on planet Earth. All of them stuck inside their own brains, doomed to perceive the world as they interpret it, rather than as it is.

A thought experiment was once offered: how do I know I'm not a brain in a vat?

As in, how do I know I'm not this guy:

But today, to a large extent, I believe, the problem has been solved.

Human beings - indeed all living organisms with brains - are brains in vats (13).

The vat is your skull and physical body.

You do not perceive the world directly.

To repeat, your brain interprets information it can understand (electrical energy from sensory neurons), it doesn't interpret the world directly, and therefore can realistically be thought of as being inside a "vat".

To me, this fact is incredibly interesting, and raises all sorts of problems.

It explains, first, how two people can have the same experience but have completely different reactions.

The two people have interpreted things differently.

We walk around and interact with others. We speak and we listen, and it seems like these things happen instantly, without effort.

But in reality each of these interactions is a complicated biological process where information has to travel a long way, and then has to be interpreted.

The complexity of this has been appreciated recently, where artificial intelligence researchers have had difficulty getting their computer systems to perform normal human activities, such as deducing the meaning from a story, understanding metaphor, or driving a car (14).

It is no wonder that misunderstandings arise between people - even people who speak the same language.

Some scientists think that thought and language are fundamentally distinct entities, partly because often we can think of what we want to say, but cannot find the right words to express our opinion (15).

We think in mentalese (the language of thought), and speak in words (the physical language you can hear).

I remember a friend and former work colleague telling me about her experience of speaking a second language. Because English wasn't her first language, she spent more time interpreting things than native speakers, and other people sometimes mistook her slowness as stupidity.

For example, a joke teller tells a joke. But she just didn't get it, at least not straight away. Quite often humour is - and especially British humour - subtle, and requires paying attention to intricately small details.

"Getting" humour in a foreign language, then, is very difficult, and people would do well to slow down or alter their communication style when speaking to someone who is not a native speaker of their language.

They may not be stupid at all, but have perfectly functional mentalese (thought language), and might well enjoy the joke if it was translated into their own spoken language.

People are stuck inside their brains, and where language barriers arise, people need the benefit of the doubt!

No doubt communication between two romantic partners is often complicated by the fact that both parties are each stuck inside their own brains.

Each person carries with them their own DNA, personality, childhood successes and traumas, assumptions about the world, and how it works.

If a person cannot communicate clearly about how they feel, or about why they want to do something, or reflect on what went wrong, resentment between people is likely to build.

It is for these reasons that communication in romance is said to be probably the most important thing for sustaining a relationship over the long term (16).

An unbridgeable communication gap between people exists, and this is a problem that will continually need to be worked on and mitigated in any relationship - romantic or otherwise.

A future exists where technology may finally be able to bridge this gap, and it will likely come in the form of digital computing technology that interacts with brain cells according to the laws of physics.

In other words, brain-computer interfaces may be able to talk to each other - just as two friends "text" or "email" each other today.

Today, we think, send a message, and receive one.

Tomorrow, we may just think about sending a message, stimulating our brain-computer interface, and send it directly to somebody else's brain-computer interface, that will decode the message, and respond accordingly.

Alas, I am repeating myself from a previous post, but the prospect is frightening, real, and exciting (it's discussed in more depth here).

I believe that an unbridgeable communication gap exists between all people in all places across the world, and our use of language is an attempt (one that does not fully succeed) to bridge the gap. But in the future, technological brain-computing advances will close this gap further, and we will, to some extent, be able to communicate to each other with directly thought.

Direct communication via mentalese is, in principle, possible.

Whether is desirable or not is another question altogether, an issue beyond the scope of this discussion, but one that's obviously woeth thinking about.

Indeed, Kant's idea has some more implications - discussed next.

Kant's big idea was about interpretation.

We cannot know the world directly as it, but know only our interpretations of it.

Strictly speaking, we cannot know the world because we are all brains in vats - or bodies and skulls.

A central tension exists, then, between the extent to which the world itself is actually real, and how our brains interpret this reality.

What I mean by this is: how much of things "out-there" are interpretable (and are therefore malleable, subject to changes made by us) and how much stuff "out-there" is real (in the sense that our interpretations of it do not alter the nature of how things are, and is therefore more about recognition of real patterns in the world).

The idea that we cannot know the world directly spawned a line of thinking that was incredibly sceptical about the "real-world" end of the spectrum.

The philosopher Schopenhauer started a book with the line (17):

"The world is my idea".

And later Nietzsche would write that (18):

"There are no facts, only opinions".

The contemporary philosopher Stephen Hicks traced the roots of postmodernism back to Kant and his emphasis on interpretation (3).

Postmodernism is an influential school of thought that arose in the 1950s and 1960s, which emphasises that the modern world and the ideas on which it is built (Enlightenment thinking) is, for the most part, no longer a good idea, and that we need new ways of thinking.

They take an extreme, in Hicks' view, interpretation of Kant's position.

For example, some postmodernists have been critical of an appeal to evidence in science, believing that because everything is interpretation, what use is "evidence"?.

The debasement of evidence may also help to explain something known as "cancel culture" (19). This movement prefers to silence other humans instead of debating them with evidence.

If evidence doesn't matter - what good is debate, discussion, differing points of view, even democracy?

Cancel culture (to my mind) has it's roots in the strong interpretation of Kant's theory (that we cannot know the world directly). In a world where evidence no longer matters, how might decisions be made?

And if the appeal to evidence no longer matters, how might we discuss important issues? Abandoning a commitment to debate opens up the door to all sorts of random processes in decision making ("Why did you implement this government policy? "Oh, because it felt right". "What about this one? "Because I hate Brexit voters and wanted to impose sanctions on them").

The point is, that without debate - and a commitment to using reason and evidence - we are back to Tudor times, where Catholics were burned at the stake because they were Catholic, and Protestants were burned at the stake because they were Protestants.

Without evidence, the door is open to randomness, strong emotions, and even violent decisions that have little justification.

Questioning evidence itself, and hence reality and how it really works, opens the door to endless interpretation, and arbitrary decision-making. Reality itself (in some circles) is said to be a social construct.

And if things are a social construct, then they can be constructed differently.

Postmodern advocates sometimes align the interpretation view of the world to particular political agendas, because if things are socially constructed in a particular way, then they could be constructed differently in a different way.

This has had a profound impact on literature and art too, where postmodern thinkers are mostly found. If everything is interpretation, then there is no hierarchy of interpretations.

This means that one interpretation of Dostoevsky's literature is just as good as somebody else's.

I might read Crime and Punishment and interpret that the main takeaway message that the author wanted to convey was that all old people are evil, and that's why Raskolnikov killed the elderly lady at the beginning of the book.

In artistic circles, if interpretation is everything, then there is no such thing as beauty, since a picture of concrete is just as beautiful as a water colour of the lake district.

This is why modern art is sometimes visibly ugly to look at, because the artists themselves are trying to make a philosophical point that how things are interpreted is arbitrary. Questioning the nature of art ("what even is art, man?") seems like a good idea, but I think that the Lake District will always be more beautiful than concrete.

I personally believe a much milder version of Kant's hypothesis, which I take from Pinker's writings (20, 21).

Most effective scientists today are a bit postmodern, Pinker writes - they recognise that they don't know the world directly, that how things are interpreted is incredibly delicate, and important.

But it mostly stops there.

The world is real and it really exists. As Pinker puts it (22):

"Reality is that which, when you apply motivated or myside or mythological reasoning to it, does not go away. False beliefs about vaccines, public health measures, and climate change threaten the well-being of billions. Conspiracy theories incite terrorism, pogroms, wars, and genocide. A corrosion of standards of truth undermines democracy and clears the ground for tyranny".

It matters how we interpret things, and some interpretations are better than others.

Let's take a recent example.

Today I watched some clips of Prime Ministers questions in England where leader of the Labour Party Sir Kier Starmer congratulated new leader of the Conservative Party, Rishi Sunak, on his new job role.

Having a British-Asian Prime Minister is a first for Britain, and it embodies a belief embedded into modern British culture: it doesn't matter who you are or where you come from, you have the right to progress in life because you are human.

Kier rightly pointed out that this is not the case in countries throughout the world, where women cannot attain office, or minority groups are purposely excluded. In many countries, the socially constructed value of a "human right" does not actually exist (23).

One way I actually think about the notion of human rights is that it is a concept roughly as old as my Grandad! It really wasn't until post-World War Two that the concept was brought in and implemented at such scale in countries around the world (though philosophers would have written about it much earlier).

In others places still, doctors treat patients according to their personal judgement - guesses - about how best to treat somebody, rather than relying on boring comparison studies and statistical tests, which are designed to discover if a certain treatment works better than others (24).

Allowing people to succeed regardless of their race or background is a good idea, as is more distanced or objective decision making in health-related fields.

Regarding sensitive matters, some postmodern thinkers are quick to frame the circumstances of men and women as a kind of battle between the sexes, sometimes asserting that sex itself is a category of socially constructed reality, or a weaker interpretation asserting that gender itself is.

Again I'm with Pinker (20).

Sex differences a real. They exist, but only at the extremes (meaning there is much more similarity than there is difference).

Moreover, gender roles throughout history have tended to be relatively fixed, and here I'd agree with the postmodernists - change in strict sex roles is a good idea.

The fact that sex differences exist (or any number of other real differences in the world exist, climate change is another example) says nothing about our values, however.

Our values on these matters are crucial.

Top-down, human imposed, subjective values do not change how the world really works (like minor sex differences or climate change), but they do change our interpretations of the world, how we responded to such differences, which may then effect the world.

For instance, believing that women can enter politics means that more women probably will enter politics, where they will likely succeed just as men do. And if more people drive electric cars, then CO2 emissions will be reduced, and climate change is mitigated.

How the world changes should be up for rational debate, too. Decisions ideally should be backed by diverse viewpoints that offer competing and alternative evidence-based viewpoints.

Perhaps one reason for the rapid failure of Liz Truss and was her insistence on having a cabinet who all shared very close beliefs to her, instead of welcoming competing people with different ideas, different viewpoints, and differing lines of evidence.

Ultimately we cannot change how the world really works, but we can change our responses to how it works, making things better or worse, safer or more dangerous, more equal or more tyrannical.

We can do all this without having to believe that reality itself is a social construction, and in doing so reject the stronger (but influential) notions from postmodern thinking (another note: probably not all of postmodern thought is so radical, and I am biased in the fact that I have read more criticism of postmodern thinking than from the postmodern thinkers themselves!).

To conclude this long section, some art is better than others, and not every interpretation of Dostoevsky is equal. Science and debate relies on evidence, which is surely a good thing compared to mere interpretation, personal preferences, and opinions (the "I think this", "I think that").

Even though we are all brains stuck inside vats, even though there is a world out-there that works according to certain laws, this does not mean we need let nature take it's course in everything.

Human culture derives it's power from the ability to effect intentional change in the world, like universal education, free markets, psychological therapy, progressive social policy, and human rights (25).

This is the weak interpretation of Kant's thesis, and I think it is the right one.

Probably what is beyond debate, though, is that Kant's idea is profound, and has far reaching consequences across human domains: from the brain sciences to debates in politics.

It's an idea worth knowing about, and I hope to have done the story justice.

Remember, some story tellers - and the evidence they provide - are better than others (I believe)!

But a better message to conclude on would be this: when it comes to thinking about and acting in the world, do your own research, and make up your own mind!

1) Pinker's The Better Angels of our Nature (2011)

2) Hicks' Explaining Postmodernism (2004)

3) Harari's Sapiens (2015)

4) Durant's The Story of Philosophy (1991)

5) Taleb's The Black Swan (2007)

6) Reported in Peterson's 12 Rules for Life (2018), but was originally written by Nietzsche in The Gay Science (1882), which I am yet to read.

7) Reported by Pew Research Center in a (2019) article: Are religious people happier, healthier? Our new global study explores this question. Accessed at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/31/are-religious-people-happier-healthier-our-new-global-study-explores-this-question/

8) Reported in Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), but was originally written by Popper in The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959), which I am yet to read.

9) Deutsche's The Beginning of Infinity (2011)

10) Marcus' The Birth of the Mind (2004)

11) Dennet's Consciousness Explained (1991)

12) Pinker's How the Mind Works (1997)

13) Elon Musk in discussion with Joe Rogan, to be found at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcYjXbSJBN8&t=2775s&ab_channel=PowerfulJRE

14) Marcus' Rebooting AI (2019)

15) Pinker's The Language Instinct (1994)

16) Peterson's Beyond Order (2021)

17) Reported in Durant's The Story of Philosophy (1991), but was originally written by Schopenhauer inThe World as Will and Representation (Vol. 1818), which I am yet to read.

18) Reported in Hicks' Explaining Postmodernism (2004), but was originally written by Nietzsche in The Will to Power (1901), which I am yet to read.

19) Haidt & Lukianhoff's The Coddling of the American Mind ()

20) Pinker's The Blank Slate (2003)

21) Pinker's The Sense of Style (2014)

22) Pinker's Rationality (2021)

23) Pinker's Enlightenment Now (2018)

24) Goldacre's Bad Science (2008)

25) Dawkins' The Selfish Gene (2016)