Grayling's problems concerning knowledge

This is a semi-book review of a profound book. Here, I restate the questions that Grayling himself rose.

This post looks at 12 problems concerning knowledge that are discussed in Grayling's The Frontier of Knowledge (2021). Well, I found them interesting to think about.

These problems exist for all methods of enquiry like, for example, physics, history, and neuroscience. But they likewise exist for decisions in a workplace. The goal of enquiry is not to solve these problems, but is to plough ahead while being aware of them.

Perhaps knowledge of these problems is also useful to foster a reasonable degree of scepticism to extravagant ideas, findings, or claims. Rather than providing answers, this post mainly poses questions (many are taken directly from Grayling's work).

The 12 Problems

1) The pinhole problem

We look out at the world from our very limited and local place in space and time

We have a finite point of view allowing us a view of the universe as if looking through a pinhole positioned just at our restricted scale; do our methods carry us successfully through the pinhole?

When somebody looks through a telescope, how do they know how far out there goes? Or what about our understanding of consciousness itself, might trees and rocks possess it? We look at the world from a very limited vantage point, and this must hedge our understanding of what we think we know.

2) The metaphor problem

What metaphor and analogies are used to help us make sense of the world, of our enquiries?

Human beings contain within them immaterial souls which are immortal says one person; the brain is like a computer in that it performs a set of operations in order to execute something, says another. Our metaphors of how we explain things change over time, how well do they guide us? Might they mislead us?

3) The map problem

What is the relation between theories and the realities they address, given the analogous differences between a map and the county of which it is a map?

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging technologies can scan and see inside a person's brain, but this a map of that person's brain, not their actual brain. How close can our models of the world come to understanding the actual world?

4) The criteria problem

What are the justifications of our research programmes and approval of results?

Do our criteria appeal to truth itself or do they appeal to ‘extra-theoretical-criteria’? Do our criteria help or distort our enquiry? The Templeton Foundation awards cash prizes, for example, to scholars who can find links between science and spirituality - when the criteria are predetermined, how does that influence what people then find?

5) The truth problem

Empirical enquiry gives us fallible probabilities

That is: findings that are so unlikely as to have arisen by chance that something else must be going on, but which nevertheless remain contestable on the grounds of evidence. Does this mean that truth itself is an unattainable goal and one that we get close to with our probabilities and never actually achieve? Where does this leave the concept of truth itself?

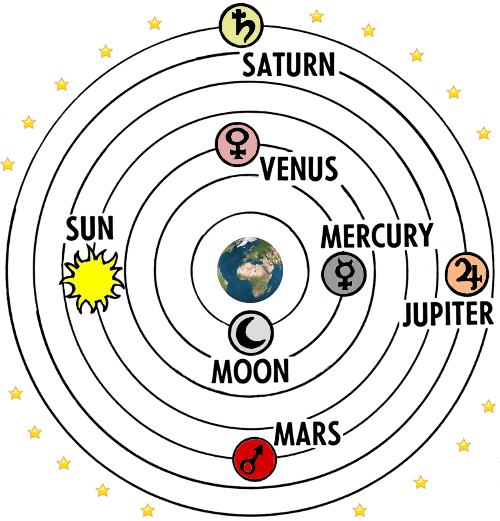

6) The Ptolemy problem

Ptolemy’s geocentric model of the universe ‘worked’ in several ways, but today we now understand it as wrong

Yes, at that time, this theory permitted the successful navigation of the oceans and predictions of eclipses, thus showing that a theory can work but nevertheless be incorrect.

But how do we avoid being misled by pragmatic adequacy? Does it matter if things work but turn out to be false? Again, how does this relate to truth? We live in a world of big data, but is more data always better?

7) The hammer problem

If your only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail

This reminds us that we tend only to see what our methods and equipment can reveal to us. Mental health problems are caused by weakness, by demons, by abuse, by genes, by chemical imbalances. What may future methods reveal?

In what other areas of life are we currently blind, but future generations may be able to see? Will our cities run on electric cars, our finance on a crypto-blockchain, and caring for the elderly reliably assisted by artificial intelligence?

8) The lamplight problem

One searches for one’s lost keys under the streetlamp at night because it is the only place where one can see.

We enquire into what is accessible to enquiry, for the obvious reason that we cannot access what is accessible Before the microscope, how did we know that bacteria existed? And before we knew of bacteria, we knew little of why disease spread (though people intuitively understood to avoid the sick). What other inventions may change the way we see and act in the world?

9) The meddler problem

We investigate something, but how do we know that we are observing the same thing when it was not being observed.

For example, when one studies animals in the wild, is one studying them as they would be unobserved, or is one studying behaviour influenced by being observed? Can smashing sub-atomic particles reliably reveal how they formed in the first place?

10) The reading-in problem

Interpretations of data are often made according to assumptions local in time and experience to the investigators.

In short, we infer things about the past, but we ourselves were not there at the time to experience it. Might this hedge our understanding how past human societies functioned and for what reasons?

Because patriarchy, because exploitation, because money, because unenlightened, because racism, because unequal, because religious etc. are all offered as explanations for why things happened the way they did in the past, or even today. And these may well be true - women in the past were outlawed from all kinds of areas in society.

But how are your present assumptions altering how you understand what happened when you were not there, and might this mean that simple explanations are unlikely to be true? When people 'read-in' to things and offer because explanations, might we gently demand better explanations, reasons, and evidence, rather than listening to who can make the most noise?

If something is important in the world to understand, and many things fall under this criterion, then a coherent argument should be presented, and should probably be done so with care, respect, self-awareness, and logic. Unlike in Monty Python.

11) The Parmenides problem

Can things be reduced to a single principle?

An ultimate, causal explanation for how things and how the world works? Would doing this be a huge mistake? This is, nevertheless, one characteristic of hard science. What is consciousness but the sum of all neural interaction? Is this an acceptable view of how consciousness arises, what it is, and what it means?

12) The closure problem

We have a desire to reach an end, a conclusion, to explain the story.

A natural human impulse is to explain things, but might we be jumping to conclusions? Or perhaps because we like to draw conclusions, we might be drawing conclusions based on limited information, which, in the long run, will turn out to be false. How can we guard against this?

The earth was once a snow globe - the sky being the ceiling. Human beings were the centre of the universe; they were distinct from other other animals. Today not only are humans understood as animals, but their place in the universe is one that rotates around a relatively small star, in a universe with billions of other stars - potentially galaxies.

Where, exactly, are we? Might there other be life out there?

The deeper problem here is the paradox of knowledge: the more we discover about ourselves and the world around us, the more we realise there is to know. Something similar happened to me as I began to read more books.

The excitement, concludes Grayling, is in attempting to answer questions like these. Though it may cause us some unease, it's okay not to have final answers to the big questions in life. The joy is in the doing.

A conclusion

These problems are said to be inherent to all forms of enquiry - of getting to knowledge.

It is interesting to think about what the future may hold. Looking back at history, even if very roughly, you get the sense that at some times things can change very quickly in the lives of people, while in other times change is scarce.

Probably our time is one of change. How might our current understanding of things change during our lives?

These problems generally refer to our limited position as humans to assess things. And these problems may very well be relevant to future generations, but the way that things are assessed and the things available to those future peoples will likely be very different.

Electric cars, space travel, decentralised finance, household robots, and personalised brain scans are all, probably, on the horizon. But these knowledge problems should serve to hedge our understanding of what we know, offer us caution, and guide our decision making.

Someone said that humans have gotten clever but not necessarily wiser. The hunting spear has become the guided missile (though, see Pinker's The better angels of our nature, 2011).

Ethical standards should - ideally - accompany growth in knowledge.