Intellectual belief #2, First principles and curiosity

Thinking from the bottom-up with child-like curiosity

This whole post is all easier said than done. First principles and curiosity are ideals to aim for, not a practice to perfect. It's something that I try to do, rather than something that I do perfectly.

School emphasises correctness, order, books. Today, class, it's books as opposed to real-world experience - again. Almost every school day its top-down rather than bottom-up learning. It's abstract, not practical. Alas, too often school makes people feel punished, wrong, and stupid for making mistakes. Curiosity killed the cat. Well, school can kill curiosity. My second intellectual belief is about education, but has little to do with school. If anything, this belief is about re-educating one's mind and leaving behind the unhelpful and excessive order which schooling so often glorifies (Note that teaching at schools is very hard and is not an enviable job. Many teachers do important and great work with young people. And while this post is critical of schooling, there are of course upsides - it's just that these aren't discussed here).

First principle thinking is a method for education. And curiosity is closely related to this. Together, they are how I try to approach my education. My two inspirations for this belief are quite different people who are known for quite different reasons. Both are somewhat controversial. One is an entrepreneur and engineer, the billionaire Elon Musk. The other is today synonymous with totalitarianism, style, and English literature lessons, the writer George Orwell. In a world where these two people meet, I doubt they would have gotten along.

First principle thinking

This belief isn't grandiose. In fact, it's supposed to simply things and be empowering. As with many things intellectual, it starts with the Greeks (1). And as with many things Greek, it began with Plato's diligent and divergent student, Aristotle. According to the internet, he is one recognised source of describing first principle thinking, but it was probably independently discovered and practiced by many different people around the world (2). What is it?

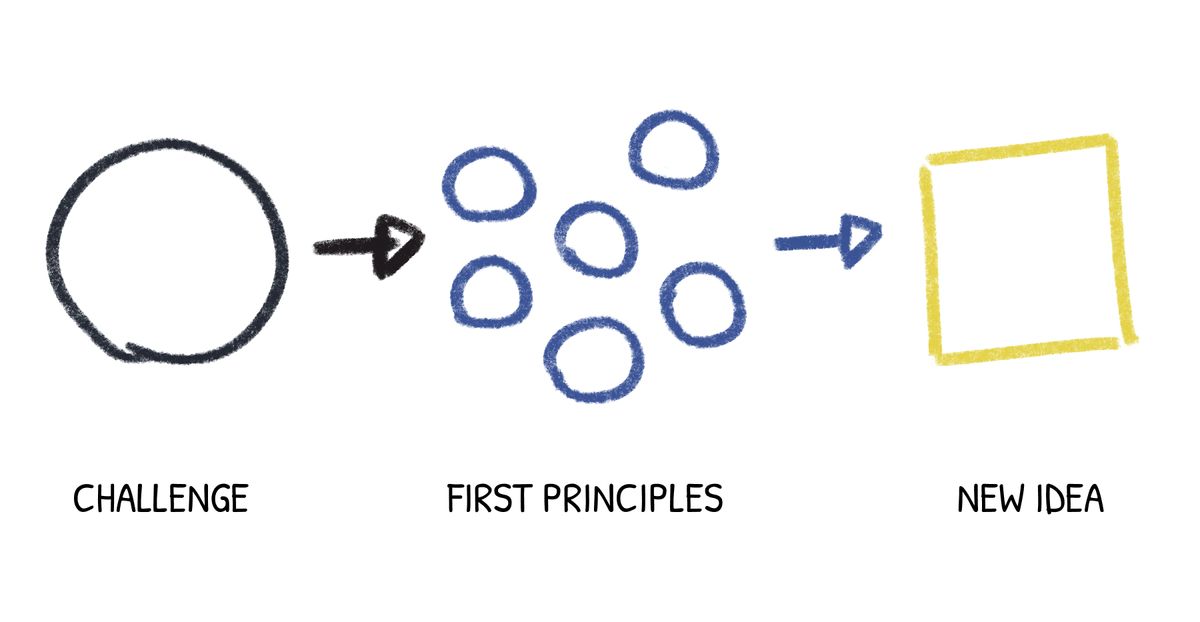

Let's say you're trying to learn something new: learning to play the guitar. A first principles approach would ask, what are the essential or core elements about learning to play a guitar that I need? Once I've broken down the problem of playing a guitar into its constituent parts (owning a guitar, listening to music, getting a YouTube teacher), I can then build up a picture of the minimum necessary requirements that this task involves. It's about questioning one's widely held assumptions and finding personal solutions to problems, tasks, or things - from the bottom-up. As the author James Clear explains (3):

[first principles] is a cycle of breaking a situation down into the core pieces and then putting them all back together in a more effective way. Deconstruct then reconstruct.

More consequential are two examples. One is about aerospace. The other is about manufacturing electric cars. Musk reports using first principle thinking to challenge long-standing assumptions in both fields (4). SpaceX, despite some recent controversy, has innovated space travel (5, 6). It now provides some of the best rockets in the world - and they now boast the biggest, Starship, which is re-useable, another worlds first. Moreover, their manufacturing process has reduced the cost going of going to space, big time. It's roughly 90% cheaper than its competitors. Then there's the automobiles. Making electric cars desirable hasn't been easy, particularly in America, which is famous for loving petrol and pick-up trucks. Texas, baby! Yet Musk's company Tesla has re-invented the industry (7). Its proven that climate-friendly cars not only work, but can be made into technologically and stylishly sophisticated machines.

In other words, by breaking down the assumptions of these two industries (space travel and sustainable transport) into their consistent parts and reasoning up from there, it has been possible to revolutionise both, and become world-leading. Importantly, it was Musk's critics who said these things couldn't and wouldn't happen. More importantly, these critics probably had impressive university degrees. More important still, Musk left university before finishing his degree, instead preferring to find an education outside school. School education, says the psychiatrist David Nutt, constrains the mind (8). While it is incredibly useful to focus on some things and not others, we often need people unconstrained by conventional schooling who are not scared to be brave, do things differently, and think - as they say at school - outside the box. First principles is one way to escape the mental straight jacket of schooling. (To say that school is a mental straightjacket is a bit strong and ungrateful! Billions of people go without school and probably would appreciate the opportunities it presents. Nevertheless, I like the poetic feel).

What attracts me so much to first principle thinking is not Elon Musk himself but the simplicity, positivity, and action-focused mindset which it encourages, even mandates. Around age 22, I discovered that I was interested in lots of things I knew little about. Psychology, genetics, and economics, to name a few. Now at age 26 I feel confident talking about all three subjects and knowing at least some of the details which they cover. And it's because of a first principled (simple, positive, action-focused) approach. School makes people feel like failures for getting things wrong. It emphasises abstract intelligence. First principles, however, encourages a child-like mindset. It says: so, you want to know or do something? Well then, go and do it. Learn as you go. Break it down. Build it up. Make mistakes. In fact, actively make mistakes! And then actively learn from them. Ask questions.

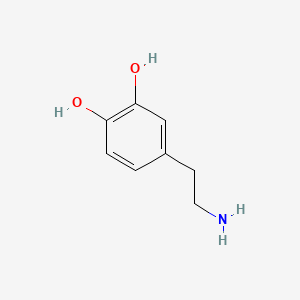

Questions like: What are the building blocks for psychology, genetics, and economics (for playing a guitar, learning to swim, becoming a writer, going to space, or building electric cars?) What are the fundamental points or steps? What do they boil down to? Who has written about this or where can I discover things? What action can I take? Questions like these lead down rabbit holes of exploration. Yes, these are the kind of rabbit holes worth travelling down. Taking action and making basic discoveries about how things work is rewarding and feels exciting. Motivation is not magical; usually it follows from taking action (9, 10). That's because we mostly experience positive emotion while in pursuit of our goals, not after we've achieved them. Sweet, sweet dopamine.

The fundamental point is that school, as is sometimes said, should not get in the way of getting an education. Nearly anyone can approach new things they want to learn or do, break things down, and then build them up in a way that makes sense to them. Anyway, all this is related to curiosity.

And therefore, to George Orwell.

Curiosity killed the communist

Communism is an idea. A mental construct abstracted from reality. An ideology. Broadly speaking, communist ideas aims to establish a better society with less greed and more sharing (11). Indeed, Orwell's own politics leaned in the direction of communism. That is, left (he settled on democratic socialism). But Orwell was critical of communism and its followers. Though in the communist writings it was proposed to re-order society for the wellbeing of all, Orwell's analysis was that communism mostly consisted of hating the rich (12). Examples of this abound. It's true that communist countries have repeatedly rounded up the wealthy and educated, put them in prison, called them class enemies, and executed them (13). This happened in Cuba, China, Cambodia, but most famously in Russia, where "wealthy" peasants were the targets (14). De-kulakization, so it goes. Hating the rich is very different to being interested in real human beings, Orwell said. And holding onto an idea called communism when it is responsible for tens of millions of deaths is, at best, bizarre.

Orwell grew up in an upper-middle class family. His father worked in the British Empire. And Orwell himself attended Eton College, the famous and expensive private school. As Orwell was going through life and developing his politics, he wanted to understand the lives of others. That is, the kind of people who don't get into Eton. But instead of reading abstract - removed from reality - communist writings and concluding: 'Aha, poor people are oppressed by rich capitalists like myself', he went out to investigate. If communism is about hating rich people, then Orwellian philosophy is about being interested in and attempting to understand real people. It's this curiosity which I admire.

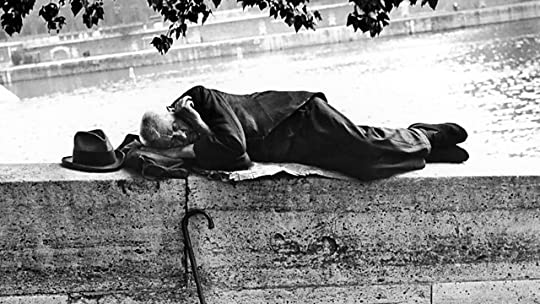

Such an outlook is detailed in three books. In Down and Out in Paris and London (1933, 15), Orwell travels to Paris around 1930, where the express goals are:

1) to live in poverty himself, and

2) to meet other people living like this.

He ends up working for some time as a kitchen porter in the Hotel X, befriends an ex-Russian soldier, and sells his possessions, multiple times, in an unfriendly pawn shop. This adventure is full of characters and their experiences living in the Parisian slums. Later Orwell returns to London where he spends time walking round and sleeping in the city with homeless people. There's dirt and hunger, hope and despair, drugs and philosophy. Above all, there's humour - and an interest in the human condition. This theme is replicated in The Road to Wigan Pier (1936, 16), which details the messy but impressive lives of English coal miners. And then there's Burmese Days (1934, 17), a novel about Orwell's time also working in the British Empire. Here, we discover his interest in Asian language and culture, while also watching him come to resent the philosophical and practical stance of Empire. All three are great books; together, they are powerful examples of an interplay between real-world and abstract experience that's driven by curiosity.

First principle thinking is about questioning assumptions and devising one's own solution to things. Curiosity can really help with this. School, unfortunately, can kill curiosity. It does this in two ways. One is by making people feel stupid for making mistakes. Of course, mistakes are the stuff of magic, and should be encouraged - especially if one can learn from them. The other is that curious students ask questions like "Why?" and teachers answer by saying "To pass your exams". Forget exams. Yes, they're useful, but being curious about things is an asset in life. Without it, there's no self-belief to ask questions, discover things, or explore what life has to offer. It was curiosity about the human condition that made Orwell into the bold writer that he was (and still is). It also killed his interest in communism, which, as he discovered and wrote about in two famous books widely (and rightly) analysed at school, is a rigid way of viewing life and human beings (18, 19, 20). It's a system of thought obsessed with abstractions. It has little care for the creative, delusional, brilliant, twisted, and curious nature of human beings. So goes the Orwellian critique of communism.

Timberrr

The lessons I take from all this are: it is better to ask questions first than to provide speedy answers; better to take action than to talk about taking action; better to be wrong and curious than right and rigid. Being curious is what leads to being wrong, which, when pursued, leads to being less wrong. Karl Popper called this critical rationalism (21, 22). In effect, it is this mechanism (being less wrong) which fundamentally describes how science and democracy each must progress. A scientific theory gets more specific and narrow, ruling out more and more possibilities. Not closer to the truth exactly, but more accurately, further away from ignorance. The paradox being that with less ignorance comes a greater realisation of how much we still have to discover. And in an election, we should not be concerned with electing the best or wisest political party. Instead, it's more important that our focus be on getting rid of terrible political actors without violence. Given enough scientific conjectures and political elections, we'll narrow our ideas down, remove terrible politicians safely, and in the process, we become less wrong (and avoid societal disasters which the Nazis and communists brought about). At least that's what Karl Popper says.

On this theme, let's finish by quoting another curious soul (23):

“Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made."

Imperfection, Kant reminds us, is a built-in feature of existence, not a bug to be ruthlessly exorcised. Thanks, Kant.

Overconfidence and rigidity in belief is a sign of intellectual immaturity. Being scared to make mistakes is a sign, perhaps, of too much schooling. Not being curious about the world is a shame, especially given that there are so many free and accessible resources these days, which certainly includes wonderful YouTube teachers. First principles and curiosity are one way to slowly build intellectual maturity. They're also great ways to approach education - or life in general. And that's why they're my second intellectual belief. An ideal to aim for rather than a practice to perfect.

References

1) Will Durant's The Story of Philosophy (1961). Accessed (probably) at www.pdfdrive.com

2) Description of First principle on Wikipedia. Accessed at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_principle

3) James Clear's article titled: First Principles: Elon Musk on the Power of Thinking for Yourself. Accessed at: https://jamesclear.com/first-principles#:~:text=Defining First Principles Thinking&text=Over two thousand years ago,Scientists don't assume anything In this post, Clear cites Aristotle's Metaphysics, which reads: “the first basis from which a thing is known.” However, I haven't read this myself.

4) In this clip of a full interview, Musk describes the process of reasoning from first principles. Accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JQXoSmC1rs&ab_channel=mahdimalek

Full interview accessed here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIwLWfaAg-8&ab_channel=TED

5) As explained by Steve Jurveston in this video titled: SpaceX and Why they are Daring to Think Big | Investor Steve Jurveston. Accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3aXNWGwis4w&ab_channel=DraperTV Interestingly, this was published 8 years ago. It has aged well.

6) The recent controversy is that SpaceX built satellites are leaking radio waves, which may be disrupting the work that astronomers can do, as described in the article: Starlink satellites flooding sky with radiation, which could be hurting radio astronomy: study. Accessed at https://www.ctvnews.ca/sci-tech/starlink-satellites-flooding-sky-with-radiation-which-could-be-hurting-radio-astronomy-study-1.6473263 It's worth mentioning that SpaceX has agreed to work with astronomers to reduce this radio wave leakage and that this problem is of a wider importance to satellite providers, not just SpaceX.

7) Many articles praise Tesla in a manner like this. My source was the article written in The Economist titled: Tesla’s surprising new route to EV domination, accessed, probably, behind a paywall https://www.economist.com/business/2023/07/18/teslas-surprising-new-route-to-ev-domination

8) David Nutt's Ted Talk titled: How can illegal drugs help our brains | David Nutt | TEDxBrussels. Accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WOxSQHtJWlo&ab_channel=TEDxTalks The conversation is basically about how psychedelic drugs can re-organise or open one mind. Nutt explains this in the context of how school can close one's mind off to possibilities.

9) Motivation follows action, a point which is discussed in Jim Kwik's Limitless (2020). I listened to this on Audible. Accessed at https://archive.org/details/limitless-upgrade-your-brain-jim-kwik/page/n17/mode/2up

10) Motivation follows action, a point which is discussed in James Clear's Atomic Habits (2018). It's a best seller and for good reason. I want to re-read this. Accessed at https://www.opportunitiesforyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Atomic_Habits_by_James_Clear-1.pdf

11) Communism addresses the problem of greed and sharing resources, as described by Marx and Engels in The Communist Manifesto (1848). It opens, to be fair, with a brilliant and memorable line: "A spectre is haunting Europe..." Accessed at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf

12) Orwell discusses hating the rich in The Road to Wigan Pier (1936). Accessed at https://files.libcom.org/files/wiganpier.pdf .

The psychologist Jordan Peterson originally brought my attention to this analysis, though I've read the original. For his analysis, this clip explains the point well https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zVJOTYzAW1U&ab_channel=JohnAnderson

13) Examples of communist violence are documented in Steven Pinker's The Better Angels of Our Nature (2012). Accessed at https://www.arab-books.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/StevenPinker-TheBetterAngelsofOurNature_WhyViolenceHasDeclined-PenguinBooks28201229.pdf

14) Examples of rounding up and executing the wealthy and educated is documented in Alexander Solzhenitsyn's abridged version of The Gulag Archipelago (1974). I listened to this on Audible, though you can access the book here https://archive.org/details/thegulagarchipelago19181956.abridged19731976aleksandrsolzhenitsyn

15) Orwell's brilliant book Down and Out in Paris and London (1932). I listened to this on YouTube, which I would recommend, since the narrator is great at doing multiple voices and accents, and this really brings the story to life. Accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ia7TuFA_opA&t=7s&ab_channel=KarinMathews

16) Orwell's The Road to Wigan Pier (1936) is half a documentation of working class life, and half a political essay. Despite being against communism, Orwell is very much in favour of democratic socialism. A great and interesting read. Accessed at https://files.libcom.org/files/wiganpier.pdf

17) Orwell's novel Burmese Days (1934). Accessed at https://zelalemkibret.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/burmese-days.pdf

18) Orwell's Animal Farm (1945). Accessed at https://ia800905.us.archive.org/25/items/AnimalFarmByGeorgeOrwell/Animal Farm by George Orwell.pdf

19) Orwell's Nineteen Eighty Four (1949). Accessed at https://rauterberg.employee.id.tue.nl/lecturenotes/DDM110 CAS/Orwell-1949 1984.pdf

20) Orwell's analysis of communism being a constraining system on human nature is discussed in Steven Pinker's The Blank Slate (2002). Accessed at https://archive.org/stream/StevenPinkerTheBlankSlateTheModernDenialOfHumanNature/Steven Pinker The Blank Slate The Modern Denial of Human Nature_djvu.txt

21) Discussion of critical rationalism in Popper's Conjectures and Refutations (1963). I am currently listening to this for free on Audible. Also accessed here https://archive.org/details/conjecturesrefut0000popp_w9h0

22) Popper's political philosophy about getting bad political actors out of office without violence is also discussed in David Deutsche's book The Beginning of Infinity (2011). I listened to this on Audible. Accessed at https://archive.org/details/beginningofinfin0000deut_u7w8

23) A quote from Immanuel Kant. I first read this via Steven Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature (above). But the quote is also accessed here https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/74482-out-of-the-crooked-timber-of-humanity-no-straight-thing