Staying sane in the October rain inside an October brain

Twelve brain-based wellbeing practices for the seasonal shift

Seasonal patterns

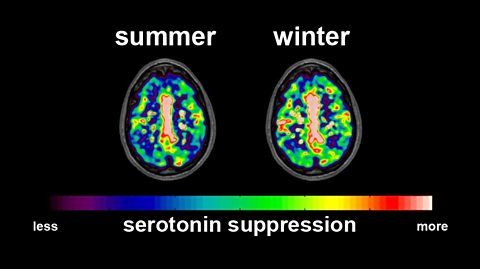

Patterns in weather often relate to patterns in mood (1). This is probably not because of changes in astrological signals, but more mundanely, because of physical changes in light and temperature. Seasonal conditions are not equally enjoyed by humans; light and warm is usually preferable to dark and cold. The most famous case is Scandinavian countries, where, before mental health services improved, had very high suicide rates (2). Today, that's improved (now their rates are rather average). Much of this despair is directly related to their nations extreme fluctuations in weather patterns. Half of the year, it is dark and cold consistently; really dark and really cold, all the time. When individuals are deeply affected by seasonal patterns like this, the term seasonal affective disorder is warranted, according to psychiatrists.

But for many who don't live in such extremely seasonal places, and thankfully including me, the slide into autumn and winter doesn't induce a psychiatric condition, though it does bring with it a certain mental gearshift. It's October in England. And the days get shorter. Outside, it gets colder, darker, wetter, greyer. Inside, my brain does the same. As we ease into the autumnal darkness, some of us have to take extra care of our autumnal brains. This post is about things I tend to practice as we each make the seasonal shift.

Here's how I help my October brain adjust to the gloom:

- Sleep, but don't oversleep. This is important because sleep supports all aspects of brain function (4). More than 8 hours isn't necessary. Less than 5 is probably too little. In the morning, I try to get out of bed ASAP, despite the coldness. This, instead of snoozing and re-entering sleep cycles, will likely help one to wake up faster. Although dreaming is crucial for our brains to process emotions, too much REM sleep, the stage of sleep in which we dream, makes us excessively tired. When dreaming in REM, our brains expend more metabolic energy than when awake and solving a complex task, like when at work. This is partly why oversleeping induces deeper tiredness rather than refreshment. Most important: I get up at the same time everyday. Doing so helps routinise the brain and body, which means better sleep. This also has a strong impact on mood. The treatment of bipolar disorder, for example, will almost universally include attempting to make sleep and wake up times consistent, such is the power of our evolutionarily ancient circadian rhythms (5). It is also easier to fall asleep in a cold rather than a hot room, because, in order to achieve sleep, our core body temperature drops by 1-3 degrees Celsius each night. And if one wants an effective way to disrupt a night's sleep, drink alcohol (6). Because of this, as we transition into darker days, I try to avoid alcohol*.

- Get outside soon after waking. I do this even if its cloudy and grey, which it will be. Exposure to sunlight is the idea (7). Photons, tiny physical particles that are made from electromagnetic radiation - what is normally called light - are ubiquitous, even on cloudy days. Getting outside specifically, for at least two minutes, reinforces our circadian rhythm, or internal biological clock, and helps us get back to sleep at night, as well as releasing helpful brain chemicals. Then, at night, I tend to avoid excessively bright lights; such things send my brain signals that it is time to wake up, instead of sleep. Receiving morning light and avoiding it come evening are both very easy ways to help an October brain's sleep, and therefore mood. More importantly, both steps are backed by appropriate scientific literature.

- Drink some caffeine. But ideally not too much. Caffeine, many studies report, has many positive effects on brain health (8). And a boost is needed in October's grimness. I try to drink it an hour or two after waking up. Because after waking, we naturally release a cascade of neurochemicals that, in fact, help to wake us up. To produce its effect of focus and alertness, caffeine blocks adenosine receptors in the brain. When we arise in the morning, our adenosine receptors have a bit of time replenish from the previous days caffeine blockage. Drinking caffeine an hour or two after waking allows our adenosine receptors time to do what they need to do - replenish. Doing this helps to maximise the benefits and minimise the downsides of caffeine. The net effect, hopefully, will be more alertness throughout the day and less of an afternoon slump.

- Take showers; first hot, then cold. I try to always finish on cold, unless it's right before sleep time. If it is before sleeping, then I finish on hot. This pattern because heat induces relaxation and helps one ease into sleep, and cold does the opposite. Deliberate exposure to cold water releases useful chemical stressors (adrenaline and dopamine), but not negative stressors (cortisol, 9). It therefore improves mood, wakes one up, helps one focus, builds mental antifragility, and at first makes one feel terrible - but then amazing. I find that it's better than coffee with less downsides. It's also an ancient practice; Seneca, the Roman senator, wrote about cold water's benefits roughly 2,000 years ago (10). And then there's the positive benefits on metabolism. After cold water exposure that we subjectively find uncomfortable, a threshold which will be different for everyone, some of our storage fat cells are converted into more thermochemically productive brown fat cells, which, among other things, produce energy, help to control blood sugar levels, and improve insulin sensitivity. To maximise the benefits, take cold showers while fasted and an hour or two after drinking caffeine (both have neurochemical effects which enhance the neurological benefits of cold water).

- Physical exercise. Walking uphill, running, and press-ups will do. Anything where one meets resistance of some kind is good. Like sleep, exercise helps with everything brain related (11). It is almost certain that humans were meant to move, at least a bit. Exercise, like deliberate cold exposure, is a perfect example of the motivation paradox (12), which is when I say to myself: "I don't feel like doing X!" Inevitably, this means that I don't do X. However, in reality, it often through doing X that I feel better, and then feel motivated. On a cold and wet and grey October day, exercise will not appeal. But many people will find that if they do the exercise anyway, despite lacking the prior motivation, what follows is a rush of feel good brain chemicals, endorphins. And then this feeling encourages one to go again. The formula is: Action --> Motivation; not Motivation --> Action. This formula applies to many things. If I am waiting for the day to feel in a good mood to write, or to apply for a new job, or to get stronger, or to do X, I might be waiting forever. But if I make a start on any of these things now - today - the motivation then follows, as does the self-respect, confidence, and overall psychological strength. Finally, exercise is particularly good in the morning before a cognitively difficult task, like doing a day's work, though personally I find that afterwards works best for me.

- After a day's work, breathe. A five minute meditation will do. I simply set a timer, lie or sit down. close my eyes, play some calming music or listen to a meditation - then breathe in for five seconds, out for nine. And repeat. Doing this stimulates my parasympathetic nervous system, the part of our body that is active when we sleep and have orgasms. Purposefully engaging this part of ourselves is relaxing and also has many neurological benefits, including: improvements in memory, focus, and reductions in stress related anxiety (13). Or, if it isn't a day for deep breathing, I just lie in a dark room for five minutes without any sensory stimulation. No phone, no light, no noise. Just darkness. And stillness. That's nice too.

- Swim, outside. I bring a hot drink and let it cool while I'm swimming. Cold showers are training for swimming outside. Wetsuits are welcome; so are neoprene gloves and shoes. This is because we lose heat fastest through glaborous skin on our feet and hands (and face, 9). Being outdoors adds a connection to nature and depth to the whole experience. But without previous practice in cold water, autumnal swimming is dangerous. It's true that the benefits of cold exist only where one has had gradual exposure. Without gradual exposure, it's unsafe. As evidence of this, a quick Google search reveals an estimate that around 250 people die each year when swimming in cold water outdoors, and most of them likely because their systems were not exposed gradually (14). Instead, their systems were shocked, sometimes for the last time. Discussing these numbers, The Outdoor Swimming society reckons that around 90% of these deaths are related to accidents, alcohol or other drug use, rather than the water itself. Moreover, they argue that one can the reduce risk massively when conscious of what they are, much like driving a car or drinking alcohol. But because this it is a bit risky, especially in these colder months, it's a good idea to swim outdoors with someone else.

- Write to oneself. An October brain can be a depressed one. And depression can be aided, though not always cured, by clear and analytical thought. Indeed, many psychological benefits exist to writing out and organising one's thoughts in a diary or in a journal. Happily, this is not my opinion, but is a statement which has been tested and then supported in many controlled experimental settings (15). If one is depressed, the first assumption must be to try and discover why; and this demands rational analysis. Time is almost never wasted inquiring into and becoming familiar with one's internal states, psychological temperament, and brain. True, a root cause may not clearly emerge, but it is good practice to attempt to understand one's emotional dips because many times understandable causes may well exist. I'd go further: accepting one's depression uncritically - without first trying to understand the nature of the beast - is a recipe for being enslaved to one's emotions, which, like the weather, come and go. But emotions, like many things in this world, can be understood. One may find answers in terrible life stressors, habits, hormones, one's unique personality, adverse childhood experiences, anger, sleep, social situations, shame, automatic thought processes or consistent negative thinking, metabolism and diet, genetics, and even, as this post discusses, the time of year. Understanding all of this starts with asking questions. Admittedly, understanding the cause of depression and emotional distress is not easy nor is it always possible, but there are usually patterns which one can observe in oneself**. Good practice is to treat oneself like a good friend. And if a good friend were depressed, I would not criticise or slate them. But humour, understanding, kindness, and warmth? Yes. From here, after rational analysis and self-compassion, action of some kind can usually follow. When feeling down, lowering expectations is a good idea, as is having some pre-planned and low energy activities to get one through the day (seeing friends, doing exercise, watching movies, listening to music, chatting with therapists etc).

- Learn; at least I try to. Personally, reading works wonders for me. An Unquiet Mind is particularly well written and compelling. Smil's How the World Works is also nice and rational and interesting. As is most things written in The Economist. Though listening is easier. Metabolic Mind, Huberman Lab, Zoe, and The Witchtrails of J. K. Rowling are the best things I've discovered or been shown recently.

- Friends! Quitting smoking is good for health. But social connections, many studies report, are also extremely important (16). The brains of friends may also be a bit depressed. It's October, after all. Talk to them.

- Do the washing up and other small tasks. The Zeigarnik effect describes how uncompleted tasks take up cognitive space in our brains and quietly stress us out (17). This is why waiters and bartenders and chefs can remember many different things all at once, but after they complete their tickets, they tend to forget what food or drinks went where. Completing small tasks brings us a small reward, and makes it more likely we'll move onto another task (12). It is easier, and often far more effective, to take small steps towards things. After all, my October brain needs little rewards to keep it going.

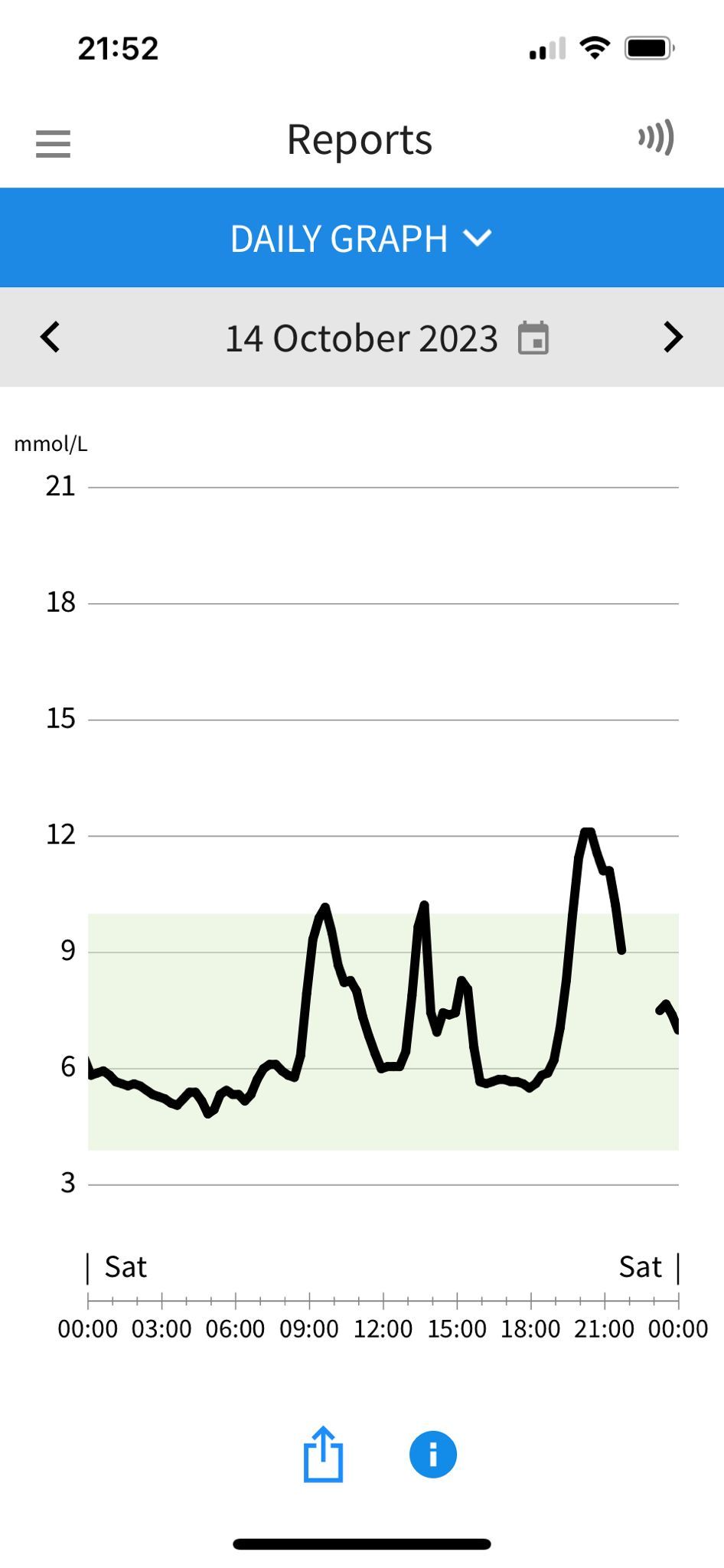

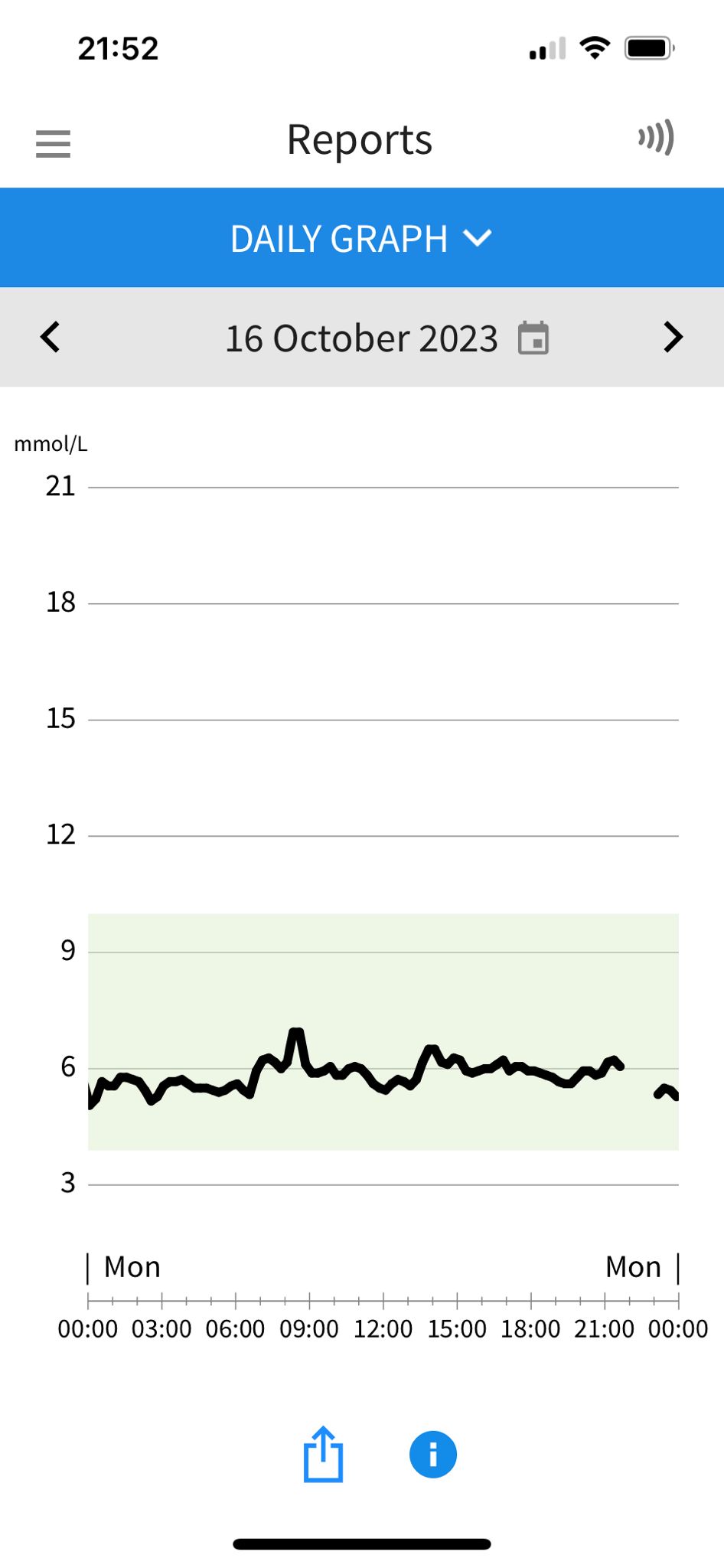

- Take food advice from a journalist, a geneticist, and a psychiatrist. First, Michael Pollen, who advocates for eating food (as opposed to edible food-like substances containing ingredients which we can't pronounce), not too much food (our ancestors weren't constantly stuffed; probably, many of us tend to over rather than undereat, and this contributes to our ills), and mostly plants (which have wide and known benefits on human health, though meat is also good; but not when it's pumped with hormones and antibiotics, and, again, our ancestors did not eat meat three times a day - nor do we need to, 18). Secondly, Tim Spectre, who advocates many things based on much ground-breaking research, like fasting until lunchtime most days, simply because this has many positive effects on brain and body (19). Also, by eating food that is diverse and different, providing it is in fact real food, we can stimulate and repopulate growth in our gut microbiome, which, when well stocked, has cascading and positive effects on human health. And then there's Chris Palmers advice, who gives evidence that a ketogenic diet, or something close to this, like minimising our carbohydrate intake, has many positive effects on brain energy (20). For one, carbohydrates tend to spike our blood sugar, which, like a rollercoaster, comes back down, and then dips below what our baseline level was before we ate. This spike and subsequent drop in blood glucose (sugar) contributes to why we feel physically tired and emotionally down.

A personal example of my own blood sugar measurements is below to demonstrate this.

Left or first image = a day of eating carbohydrates rich food (spike, crash). Right or second image = a day of eating food high in fat (balanced and lower spikes):

Supplied by ZOE's service

It is worth remembering that the brain is fundamentally a physical organ: an entity of nature that requires fuel and blood flow in order to work. It should not be surprising, then, that the fuel we choose to power our brains with directly influences how we think and how we feel about the world and ourselves. This is true because much evidence points to that fact that the mind (thoughts, emotions) is what the brain does (physical processes, 21, 22). This point about fuel can be demonstrated well by analogy. Take two cars. Obviously, the two cars will differ in how they perform depending on the kind of fuel that each has been given. And the same should be true of brains, which many scientists consider a natural machine, one that nature has, over mind-bending stretches of time, evolved. Fats, as opposed to carbohydrates, are slower release, and help to stabilise one's brain. Again, this happens because the mind is what the brain does. What this means is that the stabilising effect on the physical brain will be subjectively felt on one's thoughts processes and emotional life. Moreover, strict high fat/low carb diets, by producing ketones, regrow our mitochondria, which results in system-wide positive effects on the human being*** (20). Mighty mitochondria are important because of their influence. They involved in many things, like the gut microbiome. They are also directly involved in producing and releasing brain fundamentals: neurotransmitters and hormones. And they are involved in gene expression. And in metabolism. And where there is serious mental disease, one will usually find disturbed mitochondria. The essence is that low carb/high fat diets are good for mitochondria, and therefore, good for my October brain, which needs all the energy and stability it can get.

Notes

*Chemically, the much loved legal drug called alcohol is a depressant and a sedative (6). Because alcohol crosses the blood brain barrier, it's effects on physiology are widespread. As well as disturbed sleep, and despite providing short-term relief from anxiety, one can expect ingesting alcohol to predictably cause: a) long-term releases in the stress hormone cortisol, b) increased impulsivity, c) structural brain changes that probably occur even at moderate intake (it is neurotoxic), d) alterations in the bodies ability to effectively metabolise food, and e) a blitzed microbiome (alcohol wipes are often used to sterilise objects; inside a human, it does something similar).

If one is drinking or hungover, there are some steps to reduce the downsides:

- While drinking, eat beforehand, and drink some water while drinking.

- The day after, take a cold shower, consider eating probiotics (live yogurt or kefir, for example), and ingest food or drinks rich in electrolytes.

Together, these practices, will hopefully help to prevent hangovers or help to manage them. This is because there is evidence that each factor is somewhat effective at either preventing or helping to manage hangovers.

**Severe mental illness, as opposed to more lighter feelings of depression, appears to be characterised like a storm (23). It comes, essentially at random, and then causes carnage. Individuals must then try to ride out the storm however they can. If it is severe, riding out the storm outside of mental health services is dangerous. It's also a shame because many good and effective treatments do exist and they are worth exploring.

***Some downsides. Ketogenic or diets close to this are generally difficult to stick to (20). Moreover, the downsides are understudied and are somewhat unclear. Because keto diets mimic the natural process of fasting, it may reduce the likelihood that men and women can get pregnant if they are trying (to create a baby, bodies may need more energy than what keto can provide, though this is admittedly unclear). Specific risks also exist where medications are being taken. Note that the ketogenic diet is more accurately thought of as a medical intervention rather than as a fad. It was developed, over 100 years ago, to treat epilepsy. And it's rather effective. As a treatment, it became less used during the chemical revolution in which it was discovered that various drugs could directly alter brain chemistry, and therefore seizures, moods, emotions etc. However, in recent years, and because many chemical treatments are only partially effective for many people, the ketogenic diet as a mental health treatment is re-emerging, and is currently being studied in a wide range of ailments.

References

- Many articles discuss seasonal changes in mood. For instance: Seasonal effect—an overlooked factor in neuroimaging research - accessed at, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-023-02530-2 Or Altered resting‐state activity in seasonal affective disorder - accessed at, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6869738/

- Historically, Sweden has had one of the highest suicide rates in Europe, but this improved as did mental health infrastructure, as discussed at https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/suicide-rate-by-country

- This neuroimaging study was reported by the BBC at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/1VH3lB0NLFK2FXbPQhDkZXf/should-i-worry-about-seasonal-affective-disorder Many more imaging studies exist

- Many commentators cite sleep information from Matthew Walkers book Why We Sleep. I got my information from his Ted Talk accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5MuIMqhT8DM&t=1039s&ab_channel=TED But also, sleep is often a theme discussed in various episodes of the Huberman Lab Podcast.

- Circadian rhythms and bipolar is discussed here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uLEjoMykwh4&ab_channel=CRESTBipolarDisorderNetwork

- A physiological fact is that alcohol disrupts sleep. One can measure this if you have a smartwatch. My source for this was the episode on alcohol of the Huberman Lab Podcast, accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DkS1pkKpILY&ab_channel=AndrewHuberman

- Light in the morning is helpful for waking and avoiding bright light at night is helpful for sleeping. A topic discussed by Huberman, accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZpUe3eWKeS4&ab_channel=TimFerriss

- Effects on caffeine in the brain, reviewed at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26677204/#:~:text=In%20addition%2C%20caffeine%20has%20many,subset%20of%20particularly%20sensitive%20people. Another review here https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8202818/

- All things cold are discussed by Huberman, accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pq6WHJzOkno&ab_channel=AndrewHuberman

- Cold water exposure is discussed in Seneca's work Letters from a Stoic, accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LXq3N1rMEw0&ab_channel=AudiobookCodexat

- Exercise is good for the brain, accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6770965/

- Motivation follows action, a point which is discussed in James Clear's Atomic Habits (2018). It's a best seller and for good reason. I want to re-read this. Accessed at https://www.opportunitiesforyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Atomic_Habits_by_James_Clear-1.pdf

- Deep breathing for stress reduction, discussed in this review https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31436595/ Also, this is discussed in Haidt's The Happiness Hypothesis. And again here https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/what_focusing_on_the_breath_does_to_your_brain#:~:text=This%20study%20found%20that%20paced,regulating%20our%20responses%20to%20stress.

- The Outdoor Swimming Society discusses the numbers of deaths and the real risks at https://www.outdoorswimmingsociety.com/cold-incapacitation/ A more recent campaign urges swimmers to respect the water https://www.rlss.org.uk/news/public-urged-to-respect-the-water-as-latest-statistics-show-226-accidental-drownings-in-2022-with-more-dying-at-inland-water-than-at-the-coast

- The benefits of writing to oneself are summarised in this PDF document. It is associated with the website https://www.selfauthoring.com/ which facilitates a structured and research-based way to begin. I personally have used the structure on this site and would recommend it. But also picking up a pen and writing down one's emotions, struggles, goals, and intentions is something I find frequently helpful and at times invaluable.

- The importance of social relationships discussed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3150158/ and also at https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 and at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666535221000653

- The Zeigarnik effect, discussed at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeigarnik_effect#:~:text=Named%20after%20Lithuanian%2DSoviet%20psychologist,tasks%20better%20than%20completed%20tasks.

- A very nice and short book discusses this and more. Food Rules, written by Michael Pollen

- Much of Tim Spectre's work resides in the book The Diet Myth. Also, try out the ZOE podcast.

- Chris Palmer's thesis about metabolism and the brain is presented in Brain Energy. But these themes are also discussed online, accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjEFo3a1AnI&ab_channel=AndrewHuberman and at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JVl1X0fb1uA&ab_channel=TimFerriss

- "The mind is what the brain does". Which is a quote from Pinker's Pinker's How the Mind Works

- These themes are also discussed in Dennett's Consciousness Explained

- Severe mental illness is discussed in An Unquiet Mind.