Psychedelic drugs: rationally analysed by contemporary science, a summary in three parts

An essay on the culture and science surrounding psychedelic drugs.

Key Takeaways:

1) In the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, over one thousand scientific papers investigated the effect of psychedelic drugs in various ways, with about 40,000 research participants. The findings were generally positive, but the research was not rigorous.

2) The drugs were banned partly because they were being used to create an American counterculture; they were strongly associated with rebellion. The news cycle at that time helped to create a feeling of moral panic boosting the nation's psychology of fear towards psychedelics, over exaggerating their danger.

3) These drugs are nonaddictive, nontoxic to humans, and are considered on average safer than other drugs such as alcohol, nicotine cocaine, MDMA, cannabis, and ketamine.

3) Since 2006, science has “rediscovered” the drugs. Although still mostly illegal in the West, there is a serious evidence base building that under certain conditions they are incredibly useful for medical, psychological, and spiritual purposes.

4) The drugs are potentially of most help to people with rigid thinking patterns. This includes depression, addiction, and terminally ill cancer patients with death anxiety.

5) Brain imaging can reveal what’s going on in the brain when people are tripping, although many, many mysteries remain.

PART 1

Psychedelics meet the West

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was first synthesised in 1938, and accidently ingested mid World War, 1943. The first acid trip led to many things but early scientists were interested in it's therapeutic value and spiritual development.

It is estimated that between the early 1950s to mid 1970s over one thousand scientific papers investigated the effect of psychedelic drugs in various ways, with about 40,000 research participants.

In 1955, a banker introduced psilocybin to the West, the active part of what is known as magic mushrooms. These drugs were essentially new to the West, although they had been used by cultures around the world for thousands, if not tens of thousands, of years.

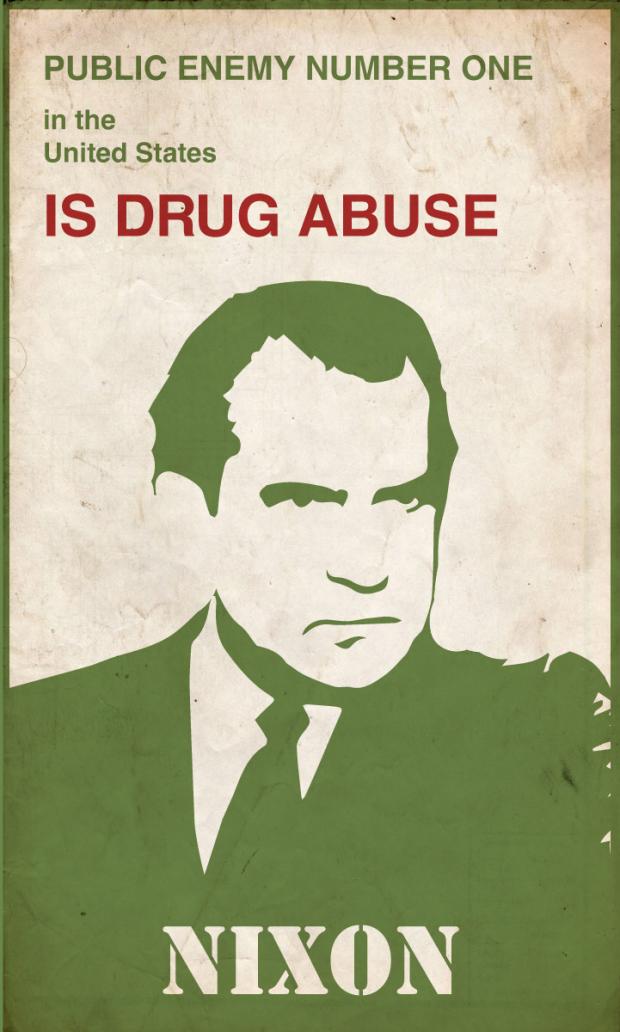

For complicated cultural reasons, the War on Drugs began in 1971 and psychedelic drugs were prohibited in the United States, by the United Nations, and mostly all around the Western world. Prohibition sent the drugs into the underworld along with all the research at the time.

Moral panic

The prohibition of psychedelic drugs around the world can be understood in the context of moral panic and the psychology of fear.

Moral panic seems to occur within a society when people position themselves against others, usually based on a serious threat to them in some way – whether real or imagined.

Moral panics seem to engage our "groupish" instincts, often bringing out the worst in people. They create binary divides: us and them, good and evil.

You’re either with us or against us.

It has been suggested and evidenced that the worst atrocities in human history have occurred when morality has been turned on. That is, when a cause has been fought, a solution offered - often said to be "for the greater good."

In the name of morality are religious Crusades, witch hunts, the Thirty Years War, the Soviet, Cuban, and Chinese communist states, together responsible for the death of 100+ million people.

One antidote to moral panic has been given by the Russian and former communist prisoner Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who has written that:

“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either -- but right through every human heart”

The idea is simply to realise the complexity of oneself before attacking another. Whether we are good or evil is perhaps not the point.

What is important is that history teaches us that bad things happen, and that, under certain conditions, you'd probably do it too - me included.

Similarly, drugs should not be evaluated as inherently dangerous or safe, but objectively assessed based on their real risks, benefits, and the context in which they're ingested.

A pub in England is setup for alcohol; a café in Amsterdam for cannabis. Similarly, a climbing gym has risk built into it - if you don't follow certain guidelines you probably will hurt yourself.

Even if you follow all the rules you can still hurt yourself! But you were informed/educated of the risks upon entry, and so you accept the risk in order to take part.

Psychedelic drugs in the 1970s were put in the evil, dangerous, and ultimately easy box, amidst a moral panic about their perceived danger.

The psychology of fear

Our best idea about the psychology of fear is as follows:

fear is driven not by what is statistically likely to happen but based on how easily we can imagine the dangerous situation, and how easily we can pull this information to our mind’s eye.

This is known as fluency.

Not all thinking is equal. Thinking through a maths problem is slow, emotion is fast. Rapid in fact.

Psychologists measure emotions through skin conduction/sweat or pupil dilation. For example, if you show people images of snakes at such a speed that they can't even recognise they've seen a snake, they will present sweat, and hence fear!

Our brains are built in layers, such that the further you travel "down", the more similar we become to our fellow vertebrates. We share with all animals an incredible similarity in nervous system, brain structure, and DNA.

For example, a recent climate scientist cited a statistic estimating that we, as humans, share 37% of our DNA with bacteria, and that 66% of our DNA is approximately 500+ million years old.

A general rule is that the older systems are responsible for the heavy lifting, and they operate at incredible speeds. Our newer systems, like the neocortex and presumably consciousness itself, are built upon efficient, ancient, lightning quick systems.

This image made your pupils dilate before you were even aware of it! Thank you systems.

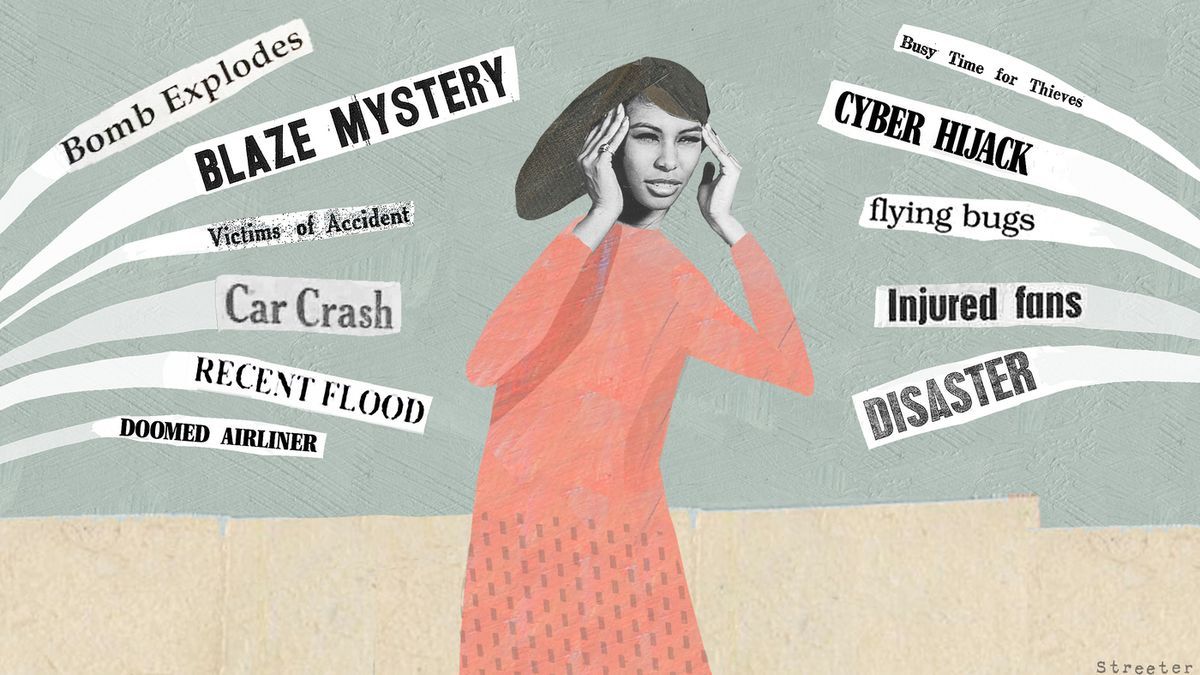

Our fluency is fastest for negative information, such as negative events in the world like terrorism or dangerous drugs. It makes evolutionary sense to be wired to spot danger and react accordingly.

Indeed, in the natural world, threat sensitivity keeps an organism alive when the danger is real. For example, we know that one of the reasons the flightless bird - the Dodo - went extinct was because it had no natural predators and was poorly adapted when predators in the form of European sailors arrived.

That said, dodos were not completely dumb.

Influences on fluency: Priming

Fluency is sped up by priming. Priming is the presentation of information like news stories or advertising (Oh how easy it is to remember “I’m Lovin’ it!”).

The feedback loop is as follows:

1) negative information primes your mind by speeding up your ability to access scary mental images, like people overdosing on LSD

2) your ability to create this mental image rapidly and imagine it playing out vividly determines your level of fear, “ban LSD!”

It was easy to imagine a person taking a tab of LSD/Acid and being left crazy for the rest of their lives. Indeed, news stories circulated about the danger of effect of the drugs: people going crazy or committing suicide.

Regularly watching the news about the danger of psychedelic drugs will prime your mental systems to orient towards potential drug dangers in the world. The danger here being psychedelic drugs.

Another example is terrorism.

I can remember being on a subway train in France age 19, around the time of a terror attack, when a brown skinned man started speaking some kind of prayer in a foreign tongue. Because it was quiet he seemed especially loud. I was terrified and got off as soon as I could.

It's not rational, it's survival. But probably still discriminatory, challenge yourself!

The consciousness of people in the United States in the 1960s and 70s was drawn to the danger of these drugs, and prohibition followed. They were primed by the media and dangerous drugs images fluency came to mind at rapid speed.

Again, your fear is not based on reality (what is the likelihood of experiencing danger?), but on an evolutionary cause of how your mind works (my mind needs rapid access to negativity to survive).

A further point is that your brain and nervous system cannot easily tell the difference between what is imagined, and what is real. For this reason, anxiety can be seriously crippling to people – especially if they are naturally imaginative.

Also, that's why "fake it till you make is pretty good" advice.

To watch or not watch the news in times of danger?

Not watching the news will blind you to the dangers of the world and you will walk around like the Dodo - naïve and vulnerable to danger. Then again, your imagination is not equal to the real danger in the world.

People get scared of terrorists attacking their cities because they’ve been helpfully informed/primed by the news, but the news hasn’t told people about driving to work – which is far more dangerous based on the number of accidents and deaths per year.

This isn’t a conspiracy, some things are simply more newsworthy than others.

Moral panics go wrong when there is a mismatch between the actual danger in the world and our fluency to imagine that danger. News cycles drive priming and fluency, while paradoxically informing people about real risk.

But because people are primed constantly, they overestimate the risk of said thing (e.g., terrorism, psychedelic drugs, and to some extent COVID-19 today).

Why were the news reporting negatively about psychedelic drugs?

Many of the fears at the time are in fact reasonable. The psychedelic advocates were creating a counterculture, explicitly promoting the drugs to change people's mind about the Vietnam War, strict societal norms, and American culture itself.

It’s also true that there really do seem to be some dangers inherent in the drugs, and people were hurt, went into psychoses, or committed suicide.

Perhaps the biggest problem with the drugs was that they went from being studied under relatively stable conditions, to being widely available to people with little consideration for how people ought to use them.

Lack of education about how to use them and a feeling of revolution meant safety was out of the window and people experimented freely, for better and for worse.

Danger is real, but it is a rational question of how dangerous

In times of fear and panic, there are rational reasons to be scared because there is real danger out there. But rational analysis is needed to determine how dangerous something is, rather than how easily we can imagine it being dangerous.

It takes time for panic and fear to subside.

Once it has, rational analysis can begin. In 2006, the time had arrived.

They’re back!

After 35 years underground psychedelics are back - under the guidance of scientific study (for many people they never went anywhere!). With care and caution, science is attempting to integrate psychedelic drugs back into our culture, rather than using them as a tool to rebel against culture itself.

Interestingly, it is those youngsters in the 60s and 70s who experimented with psychedelics and now run the research programmes. Maybe if psychedelics hadn’t been thrust out to the public with so much enthusiasm, then the Renaissance of psychedelic study wouldn’t be happening.

PART 2

Learning from “backward” cultures

Ethnographers and ethnobiologists, who study indigenous cultures and how they interact with their environments, tend to find that these people are walking encyclopaedias: there can be no doubt these people at experts of their land, often working ingeniously with the materials available to them.

The Europeans invaded the Native Americans - and not the other way around - because they had access to better animals, land, plants, materials, a geographically lengthy X rather than Y axis, trade and communication networks.

There's nothing inherently superior about being European.

It might be true that some beliefs of indigenous cultures are in fact “backward”, but the idea of backwardness often gets turned on its head.

For example, when it comes to the psychedelic research of today,

Western scientists are learning from the ancient cultures the importance of creating social norms around the drugs. Otherwise known as shamans, rituals, and purpose of use.

Set, setting, and flight instructions in modern research

Set = your mindset going in, your intention for the experience of the drug, your mental preparation, you’re awareness that what you’re about to do will probably scare the shit out of you, but the good comes with the bad. Essentially, you know at least roughly what you’re getting into.

In other cultures a Shaman would be responsible for sharing this information.

Setting = the physical place where the drugs are taken, who you’re with, who is guiding the experience, the safety precautions, time of day, inside or outside with nature and, of course, the music played.

Again, in traditional cultures, the setting is the rituals around the use of the drug.

Maybe not all bad experiences on these drugs could be prevented by paying attention to Set and Setting, but the view of modern science is that huge amounts of risk can be minimized with these simple principles. Those in 60s also paid attention to Set and Setting; it’s where the terms originally began, although it was much more fleeting.

That said, it seems incredibly likely that millions, tens of millions, perhaps even hundreds of millions of people have used psychedelic drugs outside a scientific context. There is much knowledge based between people about how to use them, but perhaps today we have a more realistic or objective view of the drugs than the excitement characteristic of the swinging sixties.

Participants in studies are informed about what the experience will be like, what to expect. They are prepared mentally, reassured that they are in a safe environment in case of emergency: that these drugs are not toxic to the brain (unlike alcohol), that a great deal of planning has gone into the experience to make it enjoyable for them, and there is a guide to be with them throughout the whole process.

Risk remains, but it is risk that is acknowledged to be built and managed.

Flight instructions = what to do while on the drug. Advice includes:

- “Climb the staircases, go wherever it takes you, float downstream, open doors, explore paths, fly over landscapes”

- “Surrender to the experience, even if it appears and feels negative”

- “Trust and let go”

- “Always move forward rather than flee”

- When encountering something scary, ask the question “What are you doing in my mind?” “What can I learn from you?”

What can brain imaging reveal about the nature of tripping

Brain imaging are technologies which allow researchers to monitor the brain in various ways, creating models in real time about what is going on inside. Often the measurements include oxygen levels or blood flow, which are both proxies for brain activity.

It is at Imperial College, London, where most brain scans have been done for people tripping on psychedelics.

Basic neuroscience

The default mode network (DMN) is the part of the brain active when you stop, close your eyes and think about yourself in relation to the world. It’s where you reflect, regret, and relive memories good or bad.

It’s the home of what has been called the soul, ego, or self.

Put simply, psychedelics really shake up the DMN.

Your brain is made up of local systems. Some interact lots, some remain separate. When you look at a picture for example, you don’t simultaneously smell the image as well as process it visually (unless it really stinks maybe?).

The visual pathway and smell system under normal conditions operate separately.

What psychedelics do is connect parts of your brain that usually operate separately.

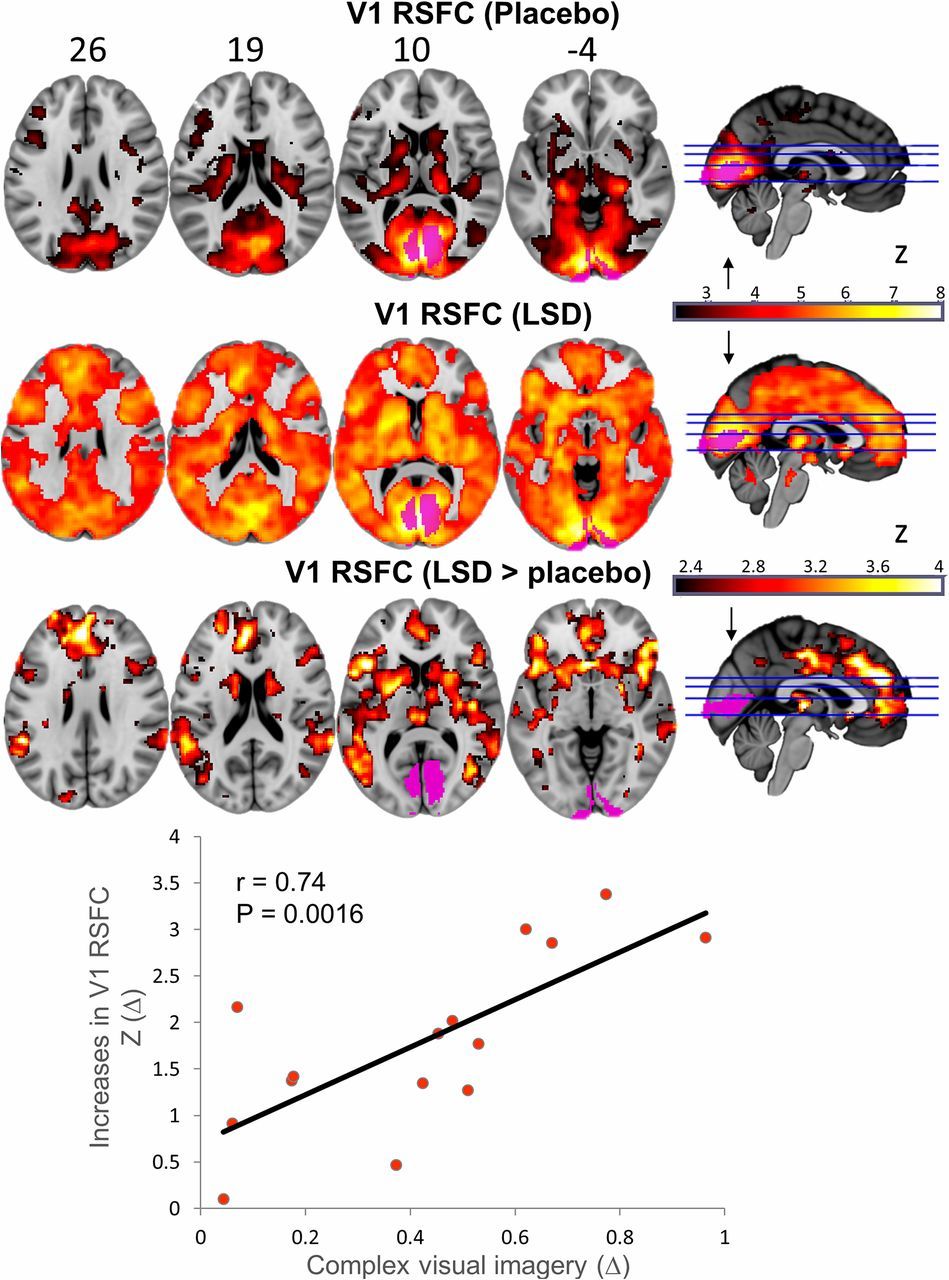

Below = the top row is the brain operating under a placebo; the second row = LSD.

When tripping, your senses interact, mingle, and connect in impossible ways in normal life. You see, hear, experience the world completely differently.

On high enough doses people experience “ego death”, which essentially seems to be the merging of their DMN with many areas of their brain at the same.

One's sense of self is reduced as the other brain pathways communicate and overwhelm what you usually think of as “myself” or “I”. What emerges from the interactions of the brain in this new way is often described as first terrifying, but later as beautiful.

Essentially, the Buddhists are partly right. When "I", or "me" dies, life goes on. Many people in psychedelic studies report describe this kind of experience as one of the most meaningful in their entire lives.

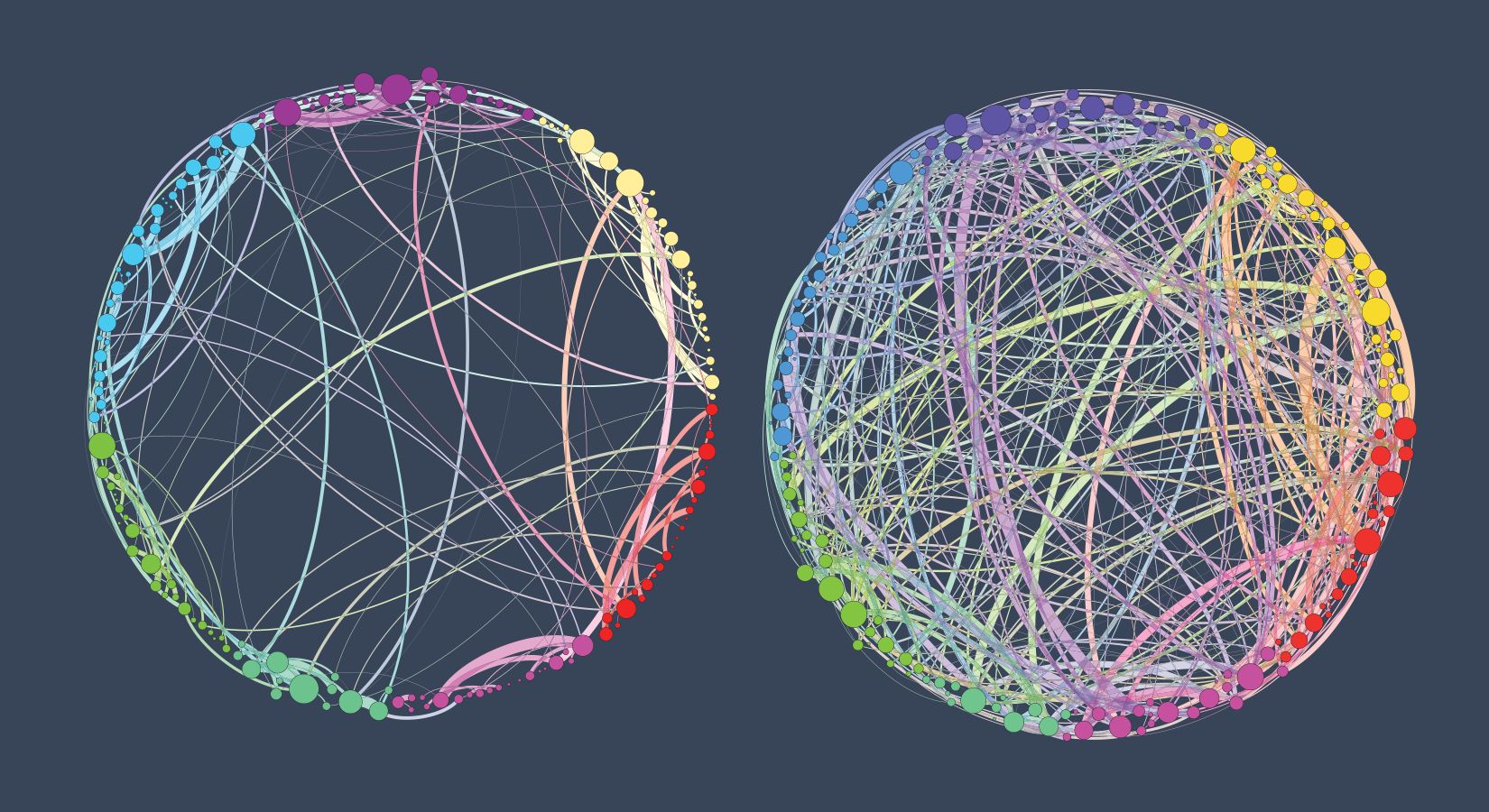

Left = a brain doing normal operations. Right = a brain on psilocybin.

Psychedelics as entropy

Entropy is defined here as describing the uncertainty about the state of a system. Gas inside a container will have low entropy, we can measure and understand what is going on inside.

Release the lid from the container, the gas will escape and fly off in all directions. Entropy increases, and our ability to rationally predict where exactly that gas is becomes increasingly difficult.

Ingesting psychedelic drugs can be seen as introducing entropy to the brain systems.

One neuroscientist described it as “shaking the snow globe”.

What science is trying to do now is work out who’s brain could benefit from temporarily benefit from increased entropy – increased chaos, uncertainty, new ways of viewing the world and themselves.

Rigid thinking patterns and therapeutic value

The most compelling idea is that introducing entropy could be incredibly useful for people stuck in rigid thinking patters. The candidates are as follows:

1) Depression

2) Addiction

3) Anxiety about inevitable death due to terminal illness

Depression

Depression is characterized by an overactive DMN. People overthink, ruminate, and evaluate themselves poorly across life. Life feels slow, like a shadow looms over them.

There is a feeling of repetitiveness, pointlessness and a heaviness to depression.

Addiction

Addiction describes the fact that some people develop an involuntary relationship to a certain behaviour or drug. They do this in the knowledge that they know it is bad for them.

Smokers know it’s bad for them, gamblers know they’re losing money. Yet they carry on regardless.

Addiction truly does become involuntary; people will pursue their behaviour or drug at the expense of all else. It is not just a matter of willpower, but largely genetic endowment, brain structure, and social environment.

Death anxiety

Death anxiety in terminally ill patients like cancer patients are looking at the world with the knowledge that they have only a year left to live. It is not surprising that this creates anxiety for them and their families.

It is not difficult to see how “shaking the snow globe” for an afternoon could be helpful for somebody in this situation.

Ingesting a psychedelic drug in the appropriate context could introduce some chaos into the person’s brain, granting them new perspectives or insight into themselves or life.

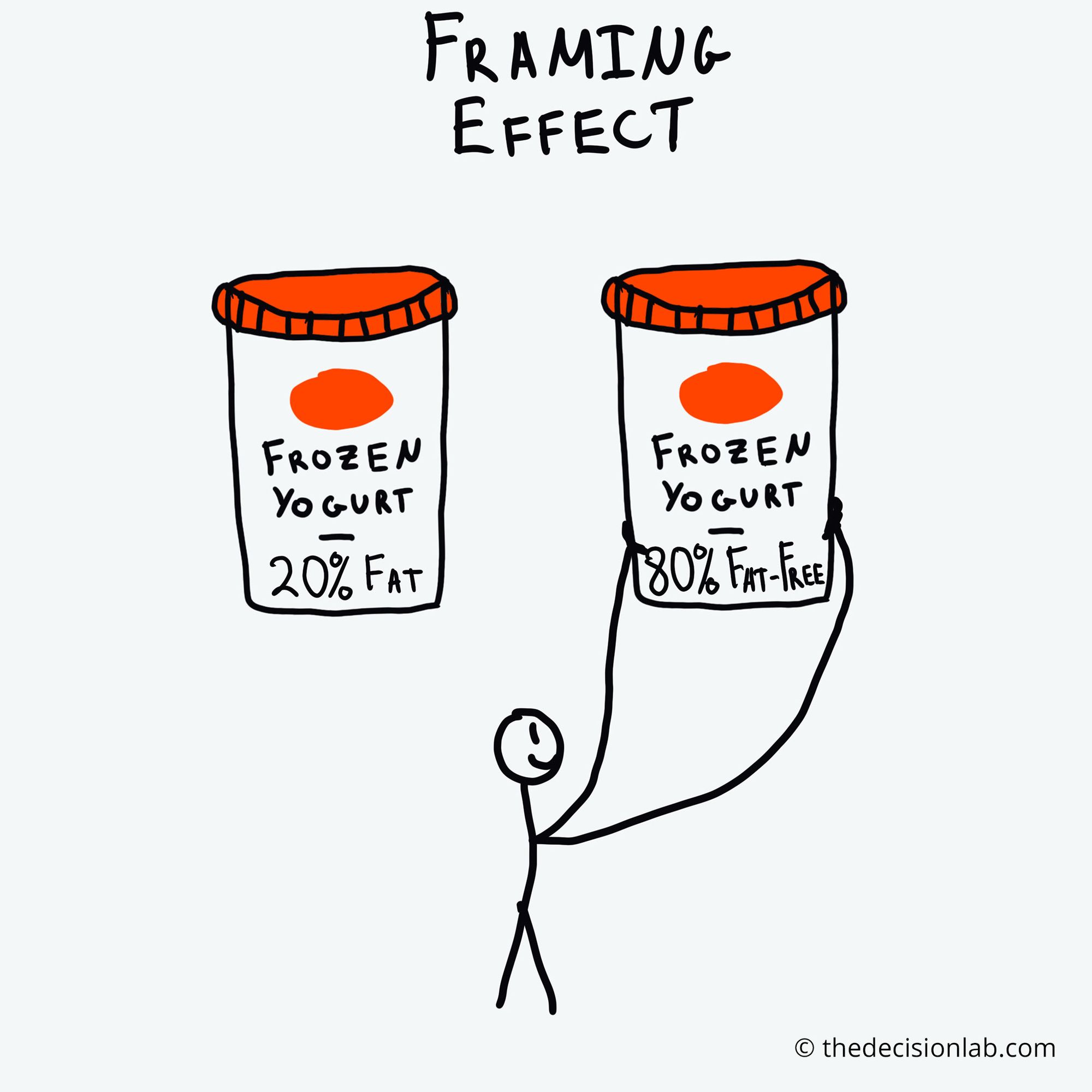

Framing in everyday life, then in psychedelic life

Framing is powerful. The framing effect in psychology sums up the evidence that how things are presented how we see, hear, and interact with information.

For example:

Positive Frame – You have a 90 percent chance of surviving the operation.

Negative Frame – You have a 10 percent chance of dying during the operation

Same information, different frames.

Another from your local supermarket:

Visual frames:

Which image is more eye-catching?

Yeah, pink!

How we frame our lives is said to be really important. Two people can experience a significant event in life like the death of a parent but react rather differently.

This is in part down to how it is framed.

What is interesting is that people have different baselines of optimism: some people are wired to always look to the positive frame! This can be pretty annoying, but reframing things can probably be learned, to some degree.

High dose psilocybin as reported in the studies leads to a kind of reframing effect.

An analogy is the astronaut who goes to space, sees the earth as a sphere floating in space and is completely blown away. Their worldview is reframed enormously.

Before, Earth was an abstract concept in the mind of the astronaut. Now, Earth is witnessed physically in space; it is seen now as precious, finite, with inhabits of an equal humankind regardless of their cultural differences.

Psilocybin seems to do something similar. People emerge with totally new perspectives on life, on themselves and their behaviour.

PART 3

What are drug addictions?

The Diagnostic and Statistics Manual (2013) defines addiction as a cluster of cognitive, behavioural, and physiological symptoms indicating that the individual continues using the substance despite significant substance-related problems.

The current thinking in science is that drug addiction is basically a disease, not a moral failing of the individual.

People have different brains, and respond differently to drugs. Some people really are set up from birth with a brain that "draws" them towards, or leaves them vulnerable to drug addiction.

Behavioural geneticists estimate that drug addictions are about 40-60% heritable. That is, up to 60% of the reason why some people get addicted to drugs and others don't is because of inherited DNA differences.

There are also many social predictors for drug addiction such as being male, transitioning into adulthood with increased freedom, early trauma and adversity, poverty, and having low school commitments.

All of this implies that we should do what Portugal has done: decriminalise possession of small amounts of drugs, and offer people support - rather than locking people up.

Psychedelics and depression

A 2015 surveyed 190,000 people in the USA about their psychedelic use and mental wellbeing. I'll let them speak for themselves:

"lifetime classic psychedelic use was associated with a significantly reduced odds of past month psychological distress, past year suicidal thinking, past year suicidal planning, and past year suicide attempt, whereas lifetime illicit use of other drugs was largely associated with an increased likelihood of these outcomes."

The studies using psilocybin to treat depression and going around America and Europe right now.

3 months ago a study concluded using psilocyin to 20 people who on average have been living with depression for 18 years. They are classified as "treatment resistant" depression because they've tried antidepressants, talking therapies, and in general their feeling remains.

They state:

"All patients showed some reductions in their depression scores at 1-week post-treatment and maximal effects were seen at 5 weeks, with results remaining positive at 3 and 6 months....The drug was also well tolerated by all participants, and no patients sought conventional antidepressant treatment within 5 weeks of the psilocybin intervention."

We'll find out the results of further studies in the next few years!

Psychedelics and alcohol use disorder (alcoholism)

One meta-analysis examined studies where LSD was administered to alcoholics in the 1960s, concluding that the results were comparable to contemporary 21st century treatments.

These studies were not the best, and it's likely that their assessment is on the cautious side. We are now beginning to run better studies applying LSD and psilocybin to alcoholism, and again getting encouraging results!

A more recent paper concludes that the intensity of psilocybin's effects predicted decreases in craving and increases in less drinking, with no adverse effects. And that:

"These preliminary findings provide a strong rationale for controlled trials with larger samples to investigate efficacy and mechanisms."

Psychedelics and Smoking

Psilocybin has also been studied to treat smokers. The smokers in the study are people who have been doing it a long time, and have been unable to quiet.

What the study found was that, after a high dosage of some psilocybin, 80% of participants had ceased smoking 6 months, and 60% cessation at 16 months.

For comparison, other interventions typically demonstrate less than 31% abstinence at 12 months, meaning that the effect psilocybin produced is the best anti-smoking treatment ever published.

Survey data

A 2010 survey of 600 people asked about the benefits and harms of their experience with drugs like alcohol, cannabis, MDMA, and psychedelics. They conclude:

"Overall [compared to the other drugs surveyed], LSD and psilocybin were regarded as having the positive impact on wellbeing, and the least harms in terms of physical and mental health"

On the negative side:

"1.3% (six of 463) of LSD users, and 0.8% (four of 503) psilocybin users reported symptoms of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, and no subjects mentioned flashbacks"

It's worth mentioning they didn't include a definition of this disorder, so people were self-reporting on things not well defined. It isn't clear that this a major concern. In fact, the research is needed to evaluate what the real risks actually are, and who is more prone to, or protected from them.

The paper concludes:

"respondents perceive the classic hallucinogens, LSD, and psilocybin, to have relatively less potential for harm than alcohol, cannabis, MDMA, and ketamine, and a notable potential for benefit... it is interesting to consider therefore why they are often regarded as particularly dangerous drugs."

The people themselves reported on how the drugs helped them with things like:

"Psilocybin made me very happy and I was not depressed at all for at least a week or two after I had taken it. (Male, aged 26, Denmark)

Once seen through the lens of LSD I quit opiates after a 15 year habit. (Male, aged 46, UK)

[LSD] helped me to stop my 2 year cocaine addiction. (Male, aged 20, US)

[Psilocybin] helped me see the negative sides of alcohol use. I was heading down a road of becoming an alcoholic (4–5 days/week) but it caused me to see the bad things I was doing. (Male, aged 19, USA).

Migraines stopped the same time I tried magic mushrooms and LSD. (Male, aged 19, Australia)

LSD cured me of a most common disease: existential emptiness. (Male, aged 24, Brazil)"

While using these drugs, people are said to have gained insight, for example:

Psilocybin has helped me confront the causes of my anxiety/depression. (Male, aged 21, Canadian)

LSD was a spectacularly effective tool in allowing me to see what my anxiety was stemming from and how to deal with it. (Male, aged 16, USA)

It’s not that the LSD helped me, it helped me help myself. (Male, aged 18, USA)

[Through psilocybin] I gained insight into myself and the world. It helped me solve issues because of this insight. (Male, aged 35, Netherlands)

Spirituality, terminal illness, and psilocybin

High doses of psychedelics seem to engender experiences people often describe as spiritual. The first research paper in around 35 years into psychedelics was done with terminally ill cancer patients who were generally struggling with their condition.

The researchers found:

1) the psilocybin session eased their anxiety and lifted their mood

2) 22 of the total group of 36 volunteers had a “complete” mystical experience after psilocybin"

Further research has shown there is relationship between spiritual experience on psychedelics and positive impact of the drug.

Specifically, the stronger the spiritual experience, the greater the benefit to the person.

Limitations and caution

1) Research into new drugs and treatments tend to produce overly positive results at the start because people are keen to publish the positive findings, while not publishing the negative

2) The studies so far generally use small sample sizes, which increases the likelihood of extreme results

3) The research recruits people in a highly systematic way, screening people out they deem to be at risk, so the findings are not simply generalisable to everyone

4) The conditions that the research is done is probably very different to how most people have taken psychedelics in real life. The biggest difference, perhaps, is the fact that the researchers have a therapist there listening to, monitoring, and supporting the person while they're tripping.

People are briefed for hours about what the trip will be like, what to expect, sop they know what they're getting into. Afterwards, people go through a debriefing process where essentially they are encouraged to extract out the meaning from the experience.

5) Researchers are generally very cautious about their findings, because in the 1960s researchers were massively enthusiastic, and encouraged young people to take psychedelics with not much care or attention about how to use them.

Conclusions

There are costs to doing things like medically using psychedelics and costs to not doing things like avoiding their use: we pay a price either way. The current evidence we have suggests that we currently paying a big price for keeping them in the shadows.

There really is quite a lot of research showing that psychedelic drugs have therapeutic value for people with addictions, or who are distressed in life more generally.

A solid foundation is currently being built to say that psychedelics should be used medically, because they can help with many problems. Addiction, depression, mental health disorders are common and our solutions for them are not very good.

We need all the help we can get.

If psychedelics can be of help, then they should be used. Just like with alcohol, there are social norms or rituals which govern how to use them and how to abuse them.

The time has come to educate ourselves about psychedelics and use them with caution at scale in our societies to help alleviate mental distress.