The normal distribution

An essay on the statistical concept normal distribution. Wider implications are also discussed.

This post aims to explain what the normal distribution is in statistics, why it matters, and how it applies to the world.

This post will finish with a discussion on how normal distributions can help us understand the politically controversial discussion about the biological basis of why men and women differ, and how this creates differences in the world.

It's worth trying to understand statistical concepts to be able to contribute towards and be critical of controversial topics like this in an informed manner (1). It is, however, incredibly difficult to treat these topics with the amount of care, scrutiny and objectivity that they deserve.

This is because such differences can be linked to all sorts of historical injustices and sexist things that people really do experience. It is not my intention to discuss these matters extensively, but I do recognise their obvious importance to the discussion.

The focus here is on the statistics and how they can help us begin to understand things in the world.

My writing here is an attempt to develop my own skill in doing this. And yet, I expect to have fallen short of my own ideals and certainly when compared to the work of others who have done a better job than me in treating this topic (see references).

This is because statistical concepts are highly abstract and can all too easily be misunderstood and falsely applied to the world, especially towards emotionally charged topics, which is another reason it worth trying to understand them.

If you're interested in the statistical ways in which men and women are similar and are different, then it is worth reading broadly on why such differences exist before jumping to conclusions that simply sound right.

This post includes a reference list that are the sources of my understanding; however, my understanding is not fixed but rather is developing as I go forward.

What is a distribution?

To be "distributed" in our statistical sense simply means: things in the world are spread out, usually from low to high. For example, in school you were asked to line up from shortest to tallest. Or maybe from youngest to oldest. In both cases, the line of students stood in a line make up a distribution. We can say that the lined up students are distributed.

What is normal?

To be "normally" distributed in our statistical sense simply means: things in the world are spread out in a way that meets our assumptions. "Assumptions" mean concepts in our heads that we share.

A group of people look at a piece of paper and recognise it to be white in colour. Together they agree, and assume, that the paper is indeed white. This is a shared assumption. In statistics, we similarly have shared assumptions.

These are crucial because we all must accept these as starting points in the discussion. Things move forward only if our shared assumptions are met. Statistics break down when the assumptions are violated.

"Normal" simply refers to a shared assumption all statistical users agree on in order to proceed, which will be explained next.

What shared assumptions does a normal distribution hold?

Something in the world is distributed, like our school children lined up from shortest to tallest. But what makes them normally distributed?

First, let's assume we have 100 students lined up. Our normal distribution assumes that a majority of students will cluster around the mean (the average height of all the students), while fewer and fewer students will cluster in more extreme locations.

That is, as we get to the shorter and taller students there will be less of them compared to those students whose height is close to the group average (middle height).

Further, our normal distribution predicts that: if we add more students to the line at random and with random heights, then the same pattern will hold true.

Now, for example, we have 1,000 students in line. The majority of them are still clustered around the mean (middle) and there are fewer and fewer students the further we move to the extreme positions in the line (short and tall).

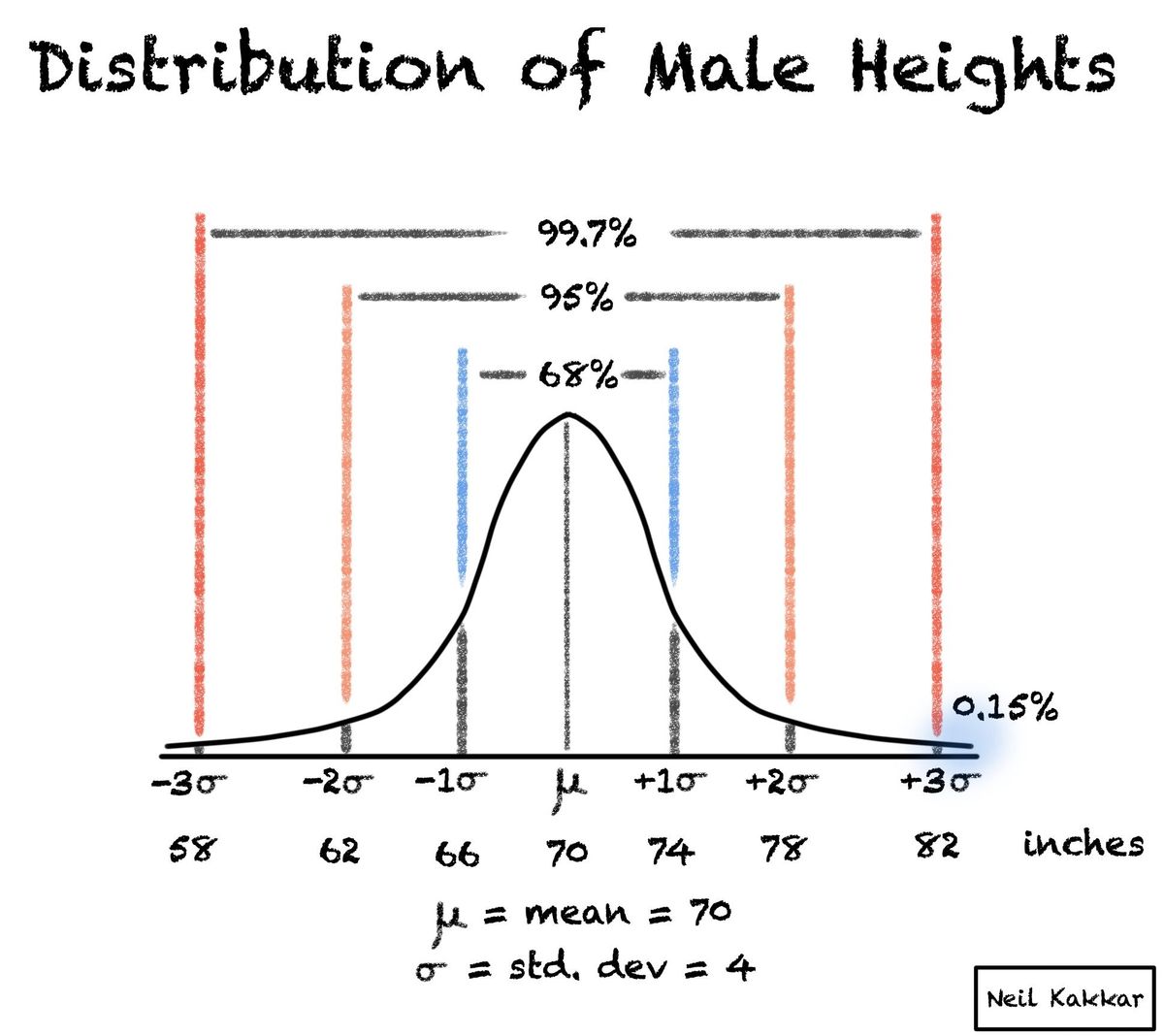

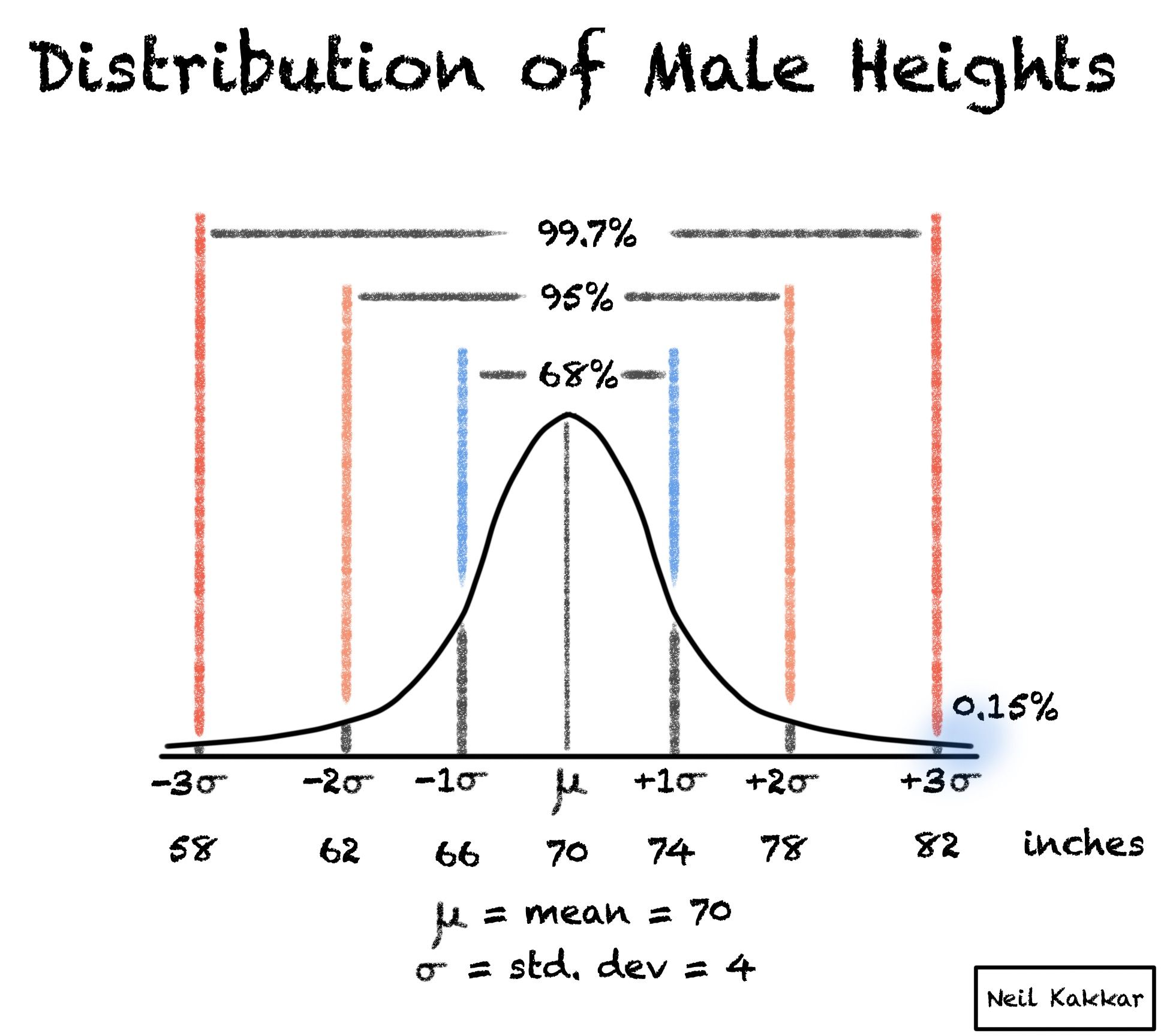

It looks like this:

The rule of thumb is that averages tend to stick close to middle and will be common, and that extremes will appear at either end of the mean (either low or high) and are rare.

Although we have 1,000 students who fall into this pattern, a normal distribution actually predicts this pattern out towards infinity. Of course, we cannot get millions of students to line up. But if we did, according to the assumptions of our normal distribution, this same pattern would continue.

To be clear, the pattern is:

1) a majority of students in the group will have a height that is near to the mean of the whole group and that

2) there will be comparatively fewer students the shorter or taller other students are compared to this mean.

How to know if things in the world are normally distributed

Another way to identify a normal distribution is to ask the following question: will one part of my distribution have a large effect on my whole? (2) Specifically, if I add one student to my line of students, will this radically alter the measurements observed?

Let's say our mean height among 1,000 students is 1.7m meters. Our shortest student is 1.2 meters and our tallest is 2.0 meters. If we add another student who is 1.6 meters, will this radically change things?

No. Because she falls within the range we already have. But if we add a student who is 10 meters tall this does radically change things! Of course, this height is impossible.

Another example is the amount of calories we all eat in a month. Let's assume we are eating 2,000 calories per day.

Now, if we eat a meal with 2,200 calories will this radically alter things? No, not really. It is higher than our expected range, but only slightly.

If we ate a meal of 15,000 calories this would radically alter things! And it would break our normal distribution. Again, this is impossible.

Opposite of normal distributions

For our purposes, we can identify the opposite of a normal distribution with the our previous question: will one part of my distribution have a large effect on my whole?

If the answer is yes, we have the opposite of something normally distributed, known as a power law, which I have written about here.

Power laws are also incredibly useful for understanding the world, especially events that take place in the social world.

Examples of power laws are: successful authors, musicians, ideas, and diseases (think how many books get written vs how many are really successful, how many songs get written to vs songs that are really popular, etc. (3).

Essentially, in each case, one small event like the sale of a really popular book, can drastically change the average.

Applying normal distributions to the world

Normal distributions are incredibly useful for understanding the world, and people should understand them - not just statisticians psychologists or geneticists. Why?

Because things in the world fall into the patterns and assumptions that normal distributions describe. We have already seen two examples: height and calorie intake.

Other examples include:

Personality traits

Information in our DNA

Physical characteristics (generally)

What can normal distributions help to explain?

If we know that things in the world fall into a normally distributed pattern, then we can understand what is going on a bit better. Below we'll look at personality research and how this applies to understanding the biological basis between men and women.

Psychologists who measure and study personality traits have found them to be normally distributed. Using the dominant theory* - the Big Five - we indeed have five personality traits (4):

Openness (interest in novelty)

Conscientiousness (hard work/organisation)

Extraversion (positive emotion/socialness)

Agreeableness (interest in people)

Neuroticism (emotional stability)

Each trait exists on a dimension. That is, a scale of more or less.

For example, if you score high on neuroticism it likely means that you'll experience frequent changes in your emotions compared with someone who scores lower, who will have more emotional stability.

What this means statistically, for example, is that on any of the big five traits we would expect a majority of people to score near the middle, while a minority will score extremely low and extremely high.

Because personality traits are approximately 50% heritable, and thus systematically created by our DNA differences, we have insight into the biological basis of how people differ in their personalities (5).

A more controversial example if the difference in trait personality scores between men and women. The dimension Agreeableness is where they differ the most (6).

High scoring agreeableness is associated with co-operation, conflict avoidance, and generally wanting to maintain relationships, to behave and think favourably towards other people - generally to see the best in people.

Whereas lower scores in Agreeableness is associated with a lack of perspective taking, willing to engage or even seeking our conflict, aggressiveness, and a general lack of interest in people, as opposed to being interested in things (machines, systems, tools etc).

This is the important point: These are statistical differences, not absolute differences (1).

If things in the world are normally distributed (like personality trait scores on the Big Five) then it means two things:

1) there is overarching similarity between these things, e.g., men and women are way more similar than they are different, and that

2) differences do exist at the extremes.

Men and women, therefore, share an overarching similarity on trait personality scores. However, at the extremes is where they differ the most.

Do these differences at the extremes matter?

Probably, yes.

It is generally thought among personality psychologists that such differences on agreeableness between men and women explain to a large extend why men and women make different career decisions.

For example, it is observed that men tend to have more of an intertest in things and hence become carpenters, engineers, mechanics, and work in other similar areas. Conversely women tend to be more interested in people and hence have more careers as nurses, therapists, social support workers, and other similar areas.

Does this mean that men cannot be interested in people or women interested in things? No, of course not.

Does it mean that our social or cultural practices exert no influence over career decisions of men and women? No, of course not.

Does it mean that there are important statistical differences in the preferences of men and women in their career decisions based on their trait personality measures, which is thought to be accounted for by 50% of their DNA, and hence we have reasonable grounds for thinking that there is a biological basis for how men and women differ in their personalities, and therefore in their work outcomes? Yes, it does (1).

Is it just biological statistical differences that matter?

No. Cultural and social factors obviously play a role in the kind of career that men or women end up pursuing or the function that either plays in society.

Historically, men have had more choice than women in such things (how many female Greek philosophers do you know?). Equality between the sexes has historically never been practiced as much as it is today, and any discussion about how men and women differ needs to acknowledge the historical asymmetry between the sexes, and how they have been treated.

A brief note on the difficulty of historically analysing differences between men and women

Yes, women have been excluded in all sorts of ways, but unfortunately this does not mean that we can simply blame men under the title patriarchy. Of course, history really is a patriarchy in all sorts of ways, and men really did seem to systematically look down in a sexist manner towards women.

All I am saying is that the term patriarchy is not good enough to explain all of the historic variance. In short, we need other explanations alongside this which are also relevant.

For example, the economic realities of people in history are wildly different to todays standards (8), so too is the supply/demand of different skills in historic workforces (8), the social philosophies(7), and the ability of women to control their own reproductive systems (9).

Sexist societies of past eras lived under different conditions to how we lived today and because of this, the factors listed here need to be considered alongside the commonly discussed (but reasonable) explanation of widespread patriarchal attitudes.

Misinterpreting normally distributed differences

Some people interpret these arguments to mean that because more men seem to prefer things and women people, men can't be therapists and women can't be mechanics, lead organisations or work in politics.

Such interpretations are lazy and patently false.

All normal distributions do is describe the world. In this case we are talking about the differences in personality trait scores between men and women. They say nothing about what should happen because of these differences.

They are also measuring things at a particular place in a particular time. If we were measuring differences in an overtly sexist society (no women allowed in politics) then we would likely get different outcomes. Culture and biology interact and influence each other; the current evidence simply suggests that the biological differences exerts its greatest impact at the extremes of the distribution.

People who hold sexist arguments such as women shouldn't become computer scientists because of inherited DNA differences and personality trait scores relying on statistical arguments have no legs to stand on. Or perhaps they simply hold sexist views and seeking to justify them.

A common mistake is to conflation of a scientific/statistical argument and a moral one, which I have written about here (echoing Pinker (10).

Essentially, what we observe with science (differences at the extreme of a distribution) are completely separate from our moral philosophy (we do not discriminate because of these differences, but treat men and women equally despite these differences).

A better interpretation

Indeed, if our cultural practices stop certain people from doing certain things, then the biological basis doesn't really get a chance to show itself.

It is only when our culture allows a much more equal basis for men and women to do the jobs they like (it's not perfect but much better than it was) does the biological basis become relevant.

Our social philosophy of equality between the sexes states that there is no good reason to discriminate between people because of their sex. That is, just because someone had a vagina or a penis is not a good reason to exclude them from a job (10). And fair enough!

Differences in things like personality trait scores between men and women should inform us about the state of the world, not divide us into hostile camps. If more women prefer to work with people, is that a problem? And if men prefer to go into work with computers, is that a bad thing?

However, should we encourage more men to become therapists, more women to become computer scientists? Yes, absolutely! Indeed, there's a wonderful argument that links the decline in violence to the fact that women are now politically empowered across the West (14)

But should we force them into workplaces? No way! At least, I don't think so.

The main reason we want to point towards the biological basis of the differences between sexes in personality scores is so that we are aware that it is not just our culture that moulds us (11). When we understand these differences, we understand the world better.

And when we understand the world better, we can have realistic expectations of it, and of the people in it (1).

The important point is that our society and culture shouldn't have unreasonable discrimination (you can't work here because of your vagina), and nor should it pretend like such differences don't exist (e.g., in personality trait scores of men and women).

Indeed. people struggler with different areas of life depending on what their trait personality scores.

For example, if women struggle more (on average) than men do in confrontation then perhaps we can use this knowledge to help women develop the skills they need to develop confrontational skills, which are essential for negotiation in the workplace or to recognise toxic relationships.

And men might (on average) struggle more so with aggression or accessing their emotions, so perhaps we could help them directing their aggression towards more productive ends or getting them to improve accessing their emotions, and thus being able to be better able to take the perspective of other people.

In short, the biological basis of personality between the sexes should help us make better decisions about who we are, not divide us into camps of biology vs culture or cause us to promote out-dated and false sexist arguments.

Perhaps on average, men and women just prefer to do different things and that's alright.

Legitimate biological differences between the sexes can easily coexist alongside a society which says: "we don't discriminate on the basis of your penis or vagina".

Personal experience of the normal distributions of differences

In my anecdotal (personal) experience I have volunteered, worked and studied in situations where the statistics of normal distributions seem to apply. I volunteered on a helpline, worked with the elderly, and am currently studying psychology.

Across all these domains the vast majority of my colleagues have been women, presumably, at least partly, because women on average prefer to do these activities compared to men. And yet I know women who are computer scientists or who work in construction, both areas of work where they are mostly surrounded by men.

As a bloke I've also been to therapy to help with things like improving my confrontation skills, because I am happen to be somebody who scores pretty high on agreeableness. Statistical differences are not to be confused with absolute differences, like good and bad or right and wrong.

It's great to have personal experiences, but studies are better. Here are some which highlight what I've been talking about (12).

A final note is that we are currently living in a time where we are increasingly sensitive to and aware of things like sexism, prejudice and discrimination between men and women. Some countries like those in Scandinavia seem to have gone the furthest in "levelling-out" the playing field between men and women.

That is, by encouraging and making it easier for men to become nurses, and women to become mechanics. We can view these attempts as a live experiment: to what extent does culture play a role in the sex differences between men and women, and to what extent do biological differences?

As stated above, the logic of biological differences states that:

as a country becomes more equal by allowing men and women more freedom in choosing their job roles, it becomes more likely that the biological differences will manifest.

In fact, there is an important difference between "equality" and "freedom".

The historians Will and Ariel Durant (13) have argued that:

1) if you want your society to be equal, you have to actively work to eliminate or suppress the natural differences between people, and;

2) if you want your society to be free, you have to accept that the differences in people will become more extreme, as people pursue the things they are interested in while others pursue different things.

Thus, if the reasoning in this post holds some validity (that the differences between men and women do exist at a biological level and exerts a meaningful statistical role on the world), then modern societies really do have a paradox on their hands:

Do we choose between equality, where we restrict differences and freedom (e.g., 50-50% of female and male politicians based on quotas enforced by law?

Or do we choose freedom, where we allow differences to manifest and accept their consequences? (e.g., no restrictions on female and male politicians and allow things to move ahead at their own accord)

Whatever path is chosen, because of our better economic standing (greater wealth), technological developments (birth control/period relief), and social philosophy (applying reason to arguments of excluding men/women) the equality between the sexes has never been greater. It is true that more women have opportunities to enter into domains they historically would not have been able to, such as into politics, construction, and the police. The converse is true for men.

As far as I'm concerned, this is a wonderful thing for the world.

And because more men and women are working in non-traditional roles, we should pay attention to the consequences and benefits that go along with this in a rational manner.

Of course, any reasonable society should not make an absolute decision between the two and instead rational trade-offs are much preferred (8). But because this is such a politically sensitive topic for all sorts of rational historical reasons, the statistical differences between men and women are likely to remain controversial, misunderstood, and unfortunately be falsely used to justify sexist arguments.

Again, it's worth trying to understand statistical concepts to be able to contribute to controversial topics like this in an informed manner (1).

Conclusion

All normal distributions do is describe the world. The occur when things group together around the mean in a majority fashion, and get rarer as they get toward extreme scores - either high or low.

Generally, physical characteristics are good examples of normally distributed things such as height, weight, or calorie intake. In each of these cases, one part does not radically alter the whole.

This is because height, weight, and calorie intake have big limitations set upon them; we don't have people over 10 meters tall or who can eat 15,00 calories a day (I think). These are patterns which follow the assumptions of normal distributions.

When we recognise a pattern of things in the world to be normally distributed, such as height or personality trait scores, we can use this knowledge to better understand what is going on.

Men and women seem to have different interests in jobs because of their differences in personality, which we can meaningfully think as biological differences (personality is 50% heritable). Thus, there is a reasonable case to made that because of these differences, and if they have freedom to choose different job roles, men and women will make different choices.

Because normal distributions mean an overarching similarity in nearly all measures, we will see these biological differences at the extremes of things where men and women differ. In personality research, trait Agreeableness demonstrates this.

It is important to understand the statistical reasoning behind claims about the biological basis of how men and women differ at the extremes of normal distributions, in order both to understand and critique them.

If people create sexist arguments and cite the literature of normally distributed statistics of how men and women differ at the extremes, then are being lazy in their interpretation of the literature, or actually hold sexist views. At the other extreme we have the school of thought that says differences between men and women do not matter, this is also wrong.

In our modern world we are creating the cultural climate to try and create equality between the sexes in various areas of work and political life. This can be viewed as a kind of live experiment to see how much culture matters and how much biology does.

Research in individual differences would suggest that as our society becomes more equal, the differences between men and women in choosing their place in the workforce will probably become larger, as they have more freedom to pursue what is interesting and meaningful to them.

It also means that more women (and men) will be able to pursue careers they historically would not have been able to do. And this is a great thing for the world.

Ultimately, knowledge of how normal distributions function should make for a more rational discussion of understandably politically sensitive topics such as the biological basis of how men and women differ, rather than inciting regressive sexist arguments or brushing such differences under the ideological carpet pretending like that don't exist.

It is completely reasonable to live in a society which accepts these differences, while also maintaining a social philosophy which actively treats both sexes equally despite these differences.

Notes

*A theory is a dangerous thing to have (3), because it simplifies the mindboggling complexity of human beings to five categories. Obviously humans are physical creatures, but a 'physics-style' theory will not be able to generate mathematical laws with people as it can in the natural world (gravity, thermodynamics etc). And yet, theories that are falsifiable (testable against other evidence) are the criterion of science; personality researchers have been doing this for over 50 years and there is validity to their work. Psychologists generally do not hold these personality measures to be a mathematical certainty but rather they represent our "best guesses" of what personality is and how to measure it. A scientific mind is a sceptical one and would not expect these personality measures to exactly capture the personality of somebody, but those who dismiss these ideas on these grounds will miss out on the explanatory power of why we measure personality - to understand ourselves, others, and the world in which we live. Personality research has many important lessons to teach, but of course we do not accept them uncritically, or radically reorganise society based on their findings.

References

1) Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate (2003)

2) Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan (2008)

3) Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Antifragile (2012)

4) Robert McCrae & Oliver John, An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications (1992) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed

5) Robert Plomin, Blueprint: How DNA makes us who we are

6) Jordan Peterson, (2015) Personality Lecture 17: Agreeableness - Aggression & Empathy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UgRaLmCOwYU&t=1s&ab_channel=JordanBPeterson

7) Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now (2018)

8) Thomas Sowell, Basic Economics, (2000)

9) Jordan Peterson, An antidote to chaos: 12 rules for life (2018)

10) Steven Pinker, How the mind works (1997)

11) Donald Brown, Human universals (1991)

12) Schmitt, D. P., Long, A. E., McPhearson, A., O'Brien, K., Remmert, B., & Shah, S. H. (2017). Personality and gender differences in global perspective: Gender and Personality. International Journal of Psychology, 52, 45-56. https://doi:10.1002/ijop.12265; Falk, A., & Hermle, J. (2018). Relationship of gender differences in preferences to economic development and gender equality. Science, 362(6412), 307. https://doi:10.1126/science.aas9899

13) Will & Ariel Durant, The Lessons of History (1968)

14) Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature (2012)