Travel creates personal economic demand

This essay is part of a series of essays on travel, where realism is my focus.

This essay is about one narrow way that solo travel is unique, interesting, and worthwhile: it creates an economic demand for yourself and others, fostering both connection and reciprocity.

This post will flesh out some basic concepts in economics, then relate them to solo travel, and try to convince you why combining them both is a good idea.

Future posts will consider a broader range of issues that surround travel, ranging from many more positives to perhaps those more realistic reasons, and importantly, the negative.

Economics and human behaviour

We must begin first with our terms, what do I mean by "economic"?

Economic first refers to economics, as in the subject academics study, and to those people who become economists. I used to vaguely think that economics was the study of 'something about money' or 'money-related'.

That's false.

Economics is not the study of money. It's far more interesting, though money is related to it. Economics is, according to the famous economist and author Thomas Sowell, the systematic study of how to best allocate scarce resources (1).

I have explained a couple of examples or options about how to think about economics in another post, but for now it's important to give an example of what I mean by resources, scarcity, and to flesh out some related concepts.

We all live on this physical earth that is made up of resources, such as: water, stone, wood, human muscle power and education; without question, all of these resources are scare - limited or finite in this context are synonyms.

Economists, then, are interested in formulas, processes and methods for understanding the ways in which living together in a human society can best allocate scarce resources. Why would it be obvious to know how best to allocate our scarce resources?

For a real world example consider your experience living in a flat or house share. If you had an experience like me, and I think like most people, when you first moved into your new flat, you quickly learned that everyone has slightly different preferences, expectations, and ways of doing things.

Something boring like doing the dishes, storing milk in a fridge, and taking the bins out taught so you something about human nature and culture: things are complicated.

Not only did people not do the dishes, but your precious milk was stolen, and there was argument over whose turn it was to take the bins out. Resources - here think of resources as the diverse array of human personalities, their preferences, and their precious cutlery- were not at all allocated well.

If you haven't experienced this, I envy you. But on the other hand, it's a great lesson in economics, politics, and psychology; reflecting on such experiences should make a person think twice about any kind of utopian idea of a perfect world and instead consider the brute reality with its mundane limitations - in this case its people arguing over their prized pots and pans.

Trivial? Maybe. But a model for the wider world? Almost definitely. The allocation of scarce resources is by no means straightforward.

And hence economics.

Supply and demand

Probably the most powerful idea in economics most people intuitively understand is supply and demand. Not only is this idea simple to understand, it is incredibly practical.

Supply and demand captures brilliantly the fact that the world is dynamic. In other words, the world constantly changes.

When it comes to the entire economy of a country, there is such a thing as too much planning. It is for this reason primarily, though also many others, that planned, state-run, or communistic countries and economies tend to fail.

Put simply in abstract terms, demand describes the fact that people need or want things. Supply is how such demands are met.

For example, the majority of scientists agree climate change is real, dangerous, and requires both our action and attention (2). A significant contributing factor to climate change is the burning of fossil fuels, which are very common in our petrol and diesel fuelled vehicles.

As this knowledge pervades civilisation, the threat of climate change and how traditionally fuelled cars makes this worse, demand is created for vehicles which can provide essentially the same service that our current gas guzzling cars provide, but that do significantly less damage to the climate.

This is where electric vehicles come in - or are supplied It is our first example of supply meeting demand.

There are many, many other examples.

Mental health infrastructure are supplied around the world to meet the demand that previous societies did not recognise, in the UK teachers are supplied better salaries to keep up with demand in the education sector, and universities supply online teaching to keep up with the demand of students continuing to attend seminars despite a pandemic, though we later realise online learning is no substitute for real life.

The mechanism of supply and demand is elegant and makes the world as we know it go round.

It is a system that puts the power in the hands of people; we are all participating decision makers in orchestrating exactly what is demanded, and what gets supplied (The purpose of this post, however, is ultimately not a lesson in economics, and you won't have to search far on the internet for various critiques of these ideas - try Behavioural Economics for some good criticism).

Economic scarcity

Another thing to understand about economic demand is: scarcity creates demand.

To put it more concretely, think back to the start of the pandemic. There was concerns about the supermarkets not having enough stuff, whether that stuff was rice, eggs, or toilet roll.

People were concerned about scarcity. What happened?

People bought out the shelves! They stocked up on rice, eggs and toilet roll. Seriously, during the first wave of corona, I think my cupboard under the stairs at home had enough toilet roll to wipe the arses of my entire extended Irish family.

Scarcity creates demand. Now, let us think about love.

What is it about that special person who is just so unavailable that makes me fancy them so much? I fancy them, but I just can't have them.

They are scarce, and it makes me want them more. This leads to all sorts of fallacies in romance, heartbreaks and unhappy scenarios; tragically, people waste time pursuing some ideal person, or at least so they think.

Alas, the person is not ideal. They are just scarce, and this helps to create your demand towards them.

And, probably, if they aren't willing to meet you halfway, they aren't someone you'd actually want to start a relationship with. And that's okay. It takes time - and in reality, often our own painful personal experience - to understand that the scarce ones are not the important ones in our lives.

What we need - what is better for us and our relationships, romantic or otherwise - is reciprocity. I want an equal relationship, where me and my partner are invested in each other mutually, not one based on scarcity and demand.

As a side note, people often seek out scarce partners because they are, for whatever personal reason - call it rational or otherwise - unavailable, and so that person knowingly can avoid any attempt at a real relationship.

Have I done this? Absolutely.

Pursuing scarcity in romance is what those of us with avoidant tendencies tend to do until one day, whether through therapy or through friends, we realise we know better. Ah, hindsight bias.

Speaking of love brings us to our final example: the sexy and scary nightlife of Berlin. During the summer of 2017 when I lived and worked there, I tried to get into the infamous nightclub, and former powerplant, Berghain.

Infamous for...? It's non-judgemental and accepting atmosphere, a cultural relic from its origins as a nightclub for gay people to express themselves when such expression was forbidden in everyday life.

At Berghain and its predecessors, clubbers could, and today still can, be themselves for a night. Within those walls judgement cannot find them; instead, expect awesome techno, sex, drugs - something the German high court recently ruled as high culture, while others call Berghain the most legendary nightclub in the world

How does Berghain do this? The bouncers have a very strict door policy.

In fact, Berghaim bouncers systematically turn away the majority of people who try to get in, and instead subjectively discriminate - choose - who to let in based on the vibe they emit.

That is, does this person fit in with the values and culture that Berghain seeks to create? Can they handle what goes on inside? Will they pass judgement?

One does need to be an economist do understand what this does.... Scarcity creates demand.

Those sexy people in the queue - and there really are some sexy people in the queue! - want to get in, BAD! In fact, there's essentially a whole online subculture dedicated to explanations of how to get in (1. Don't be drunk in the line. 2. Wear black. 3. Don't look happy. etc...)

What this does on the inside, however, is maintain the culture of no judgement, freedom, and expression; it's why the German high court considers Berghain's activites high culture, and permits them to pay the same reduced tax as local Museums.

On the outside, scarcity creates demand - expect queues of up to 4 hours at peak times to get in.

And, don't expect to get in.

Expect Sven.

Queues for days

To be fair, when I tried to get in at midday on a summer, Sunday lunchtime, walking through the suburban houses of Berlin surrounded by nature, concrete and döner kebabs, and begun to hear the faint yet deep bass of industrial German techno, and that light buzzy feeling of a brain anticipating MDMA, it did sound and feel pretty cool.

Alas, I was turned away three times. On reflection, at that time, I wasn't ready; Sven made the right call. In truth, just being in the queue was a cool experience.

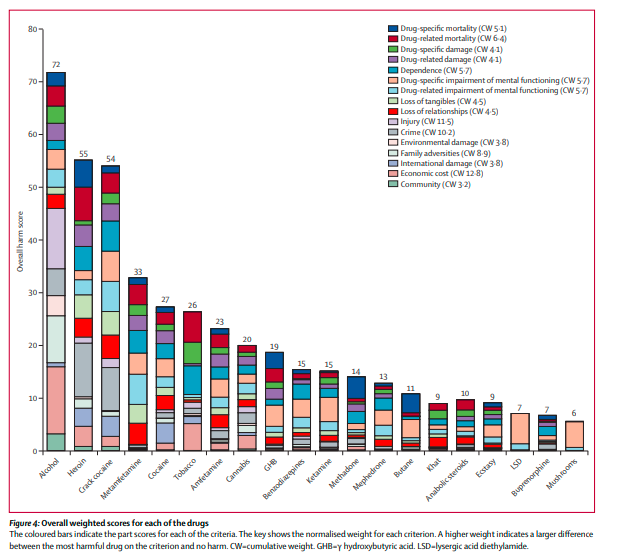

And, for the record, MDMA, is a drug arguably much safer than a drug called alcohol - but users ought to get themselves educated about the real risks that exist when you mess around with serious stuff, because, like alcohol, MDMA kills people too (3); but don't take my opinion, take the advice of drug experts - or perhaps read Drugs Without the Hot Air and take in a scientific - not moral - analysis of drugs, both legal and illegal.

These three examples - panic buying, failed romance, and a secret Berlin nightlife - all paint a negative picture of economic scarcity and demand. But are there ever situations where you would want to impose economic scarcity upon yourself to create demand?

And what does any of this have to do with solo travel?

Solo travel creates personal economic demand

In our normal lives living in the West, people, largely though not completely, have access to the things they need (4). We have access to regular work, friends, foods, housing, free time, and routine.

In general, most peoples wants and needs are supplied in one way or another.

What solo travel does is take those things and throws them out.

If you get a backpack and a bus or plane to different country with the intention of staying for a period of time, like a month, you immediately lose all of this.

First, your regular supply goes out of the window. Second, scarcity creates demand.

When I turned up in Berlin, I had no job, friends, or routine. I had free time, but didn't know what to do with it, and my house was a hostel that I shared with other people who mostly doing something similar to me.

Here, I argue that one of the main benefits of such an adventure is that it creates personal economic scarcity for you, which creates demand.

Hence, solo travel creates personal economic demand.

To get a job, I had to go out and find one. To make friends, I was forced to talk to people. To learn about things to do, I had to ask questions.

Of course, I could have done this all online: work, talking to friends, and looking up things to do. But this does not fully remove the economic scarcity of loneliness; in reality, there is no replacement for real human contact, and there is nothing better than meeting local people and getting real local knowledge, rather than following the popular opinion of trip advisor.

Going to a new place with the intention to stay for a while, perhaps to work, creates personal economic demand for you in so many ways; you will be forced for do something about this. And the great thing is that there are ways and cultures to support such a plan.

For example, the beautiful thing about a hostel is that it is a communal space designed for other people doing something similar. In practice what this means is that, if you live in a hostel on your own, you will, if you talk to people, almost certainly meet other people who have personal economic demands placed upon themselves, too.

That is, they aren't 'from here'.

They may not yet have found work, friends, or things to do - but could well be looking for all three. My experience has been that being a situation of economic scarcity, and meeting others who are in a similar position, creates an atmosphere for connection, otherwise known as demand.

Think about the opposite: you have a friend who you see fairly regularly, and then one day they are in a relationship. Sure, you still see them, catch up, but it's not quite the same.

You spend less time together, while they spend more time with their significant other. There's nothing wrong with this, intimate relationships are powerful, and important - but what happens when the relationship ends?

Probably your friend seeks connection with you. Probably you spend more time with them.

Now, people travelling alone and living in hostels are connectionless; they are in a new place void of relationships.

This is a huge economic demand upon them, and upon you. There is nothing magical about the fact that it can be so easy to connect with others when you travel alone, the economic conditions and the scarcity upon yourself and others creates such fertile ground for connection.

So, you get talking to them.

Let's imagine they do have work and, in a scenario like this, they'll likely be able to advise you about what you could do, who to talk to, opportunities to pursue, or things worth thinking about.

Better still, they might introduce you to their friends, their hangouts, the cheap supermarkets... When you're alone and seeking connection, such offers will fill you with immense gratitude - and that's without mentioning the fact that almost everything you do when in a different land feels more exciting, especially visiting supermarkets.

In social situations of economic scarcity, both people have something to gain from talking, co-operating and reciprocating with each other. When in Berlin, the Croatian hostel receptionist, for example, helped me print out my CVs for bar work and advised about the nuance of what German employers expect and do not expect, which, I believe, helped to get me employed.

Through finding work I met colleagues who informed me about interesting things to do in Berlin, which led to me learning about the city, exploring its parks, bars, and eventually combining the two (by copying many others who came before me) by selling homemade Mojitos in Mauerpark on a sunny Sunday afternoon.

To illustrate this a bit further, here's how I got to the stage where I could actually sell these mojitos.

1) Meet Lebanese lady in the hostel, get to know her over a few weeks, and talk to her about visiting this specific park.

2) Work in the Irish pub and discuss the park to other colleagues who thought it was a cool place, although a bit touristy

3) Visit the park myself and buy a beer from someone who goes round selling them

4) Get the idea to sell drinks myself next week

5) Ask an American artist in the hostel to make me a sign that advertises what I'm selling (she made a beautiful sign!)

6) Buy the ingredients from shops like Lidl and Kaufland

7) Get a spare crate from a local supermarket to store things in

8) Find a big enough freezer to store the ice because the hostel had a small freezer (this step involved me carrying a big bag of ice to a local Berlin bar and politely asking if they could store it for me and then I would come and pick it up; at first they thought I was a travelling salesman trying to sell them ice because my German was terrible, but eventually they did understand and agree!)

9) Ask a Mexican person, Ruben, in the hostel if he wanted to help me out selling mojitos in the park

10) Go to the park on the Sunday with Ruben, setting up shop on a park bench, and giving Ruben a tray of drinks to walk round and offer mojitos to people.

Here's the crowd:

All in all we made close to 100 Euros in cash. However, we ran out of ice, and, unfortunately, German supermarkets are closed on Sundays...

There is, however, nothing special about this story. This kind of story is exactly what happens to people who are out there solo travelling, who have economic scarcity placed upon themselves, and who are willing - and open enough - to create demand because of it.

If one thing is clear in those 10 steps it's that: connection was essential to make it happen.

I had to meet people and ask questions, to visit, to try things to make it all happen, and, crucially, the others all had to reciprocate. When you solo travel, you'll learn that it's people that make the experience, not the places.

These are, compared to the normal life of routine, unique circumstances. The rhythm and routine of everyday life gets completely skewed in solo travel.

It forces you to find creative solutions to problems, out of your comfort zone, and ultimately to connect with other people who are in a similar position.

To reiterate, the primary economic demand solo travels creates is loneliness. This will force you to interact socially with others OR, to remain lonely.

Importantly, because you don't have any friends, you have a real stake in making this relationship work! You have what Taleb calls skin in the game (5).

And, because you will be making friends with others who have a similar demands upon them, they'll want to make it work with you, too.

In the long run it'll probably help you communicate with people, to be authentic, and dynamic socially. When applied, knowledge is power - so, when in the hostel, make the choice to ask someone how their day was, what they're cooking, or what languages they speak.

Do so or remain lonely. This is the harsh reality of economic scarcity, of solo travel.

When staying at a friends house in Frankfurt, Germany, I was reflecting with her about how we met. In the hostel in New Zealand where we were both living, I knew nobody; loneliness forced me into conversation with people seeking connection.

I asked her something about her peanut butter, what brand she was eating, or if she liked it. Something so trivial as a simple question in conversation can spark a friendship, which, if maintained and reciprocated, can lead to one friend hosting the other at their house years down the line in their German home country.

Doing solo travel

Solo travel is not deductive, it's inductive.

That is, you cannot sit down and plan it all out with words, numbers and theory. You have to go out there and experience it for yourself, to see what emerges, and what opportunities there are.

And if you're worried about all the things that could do wrong, I think those worries are probably fair enough. Solo travel is not maths, there is no guarantee that you'll find work, connect with people, or even enjoy it.

But there are many, many things that can go right. It is only by taking the plunge and experiencing personal economic demand for yourself that you will find out if these ideas apply to your personality, values, and interests in life.

As Yoda said:

"Do or do not. There is no try"

Though, in this case, you may "do" solo travel for a number of weeks, even days. This is certainly giving it a try and the author of this post very much does recommend starting like this.

It's what I did.

And it's amazing how much action can happen in couple of days when you're out there on your own in the fertile land of economic demand, connecting with others.

Think about the reverse: lockdown. Months went by and you did nothing, time sort of blurred 'into one', and it felt like not much happened.

Try solo travel for a couple of days where you intend to meet and connect with others, or you are at least open to that possibility occurring. Assume this happens.

My experience is that the range of personalities and experiences you'll have, which are crammed into a couple of days, will make your brain feel like you've been travelling for weeks - it really can be exhilarating.

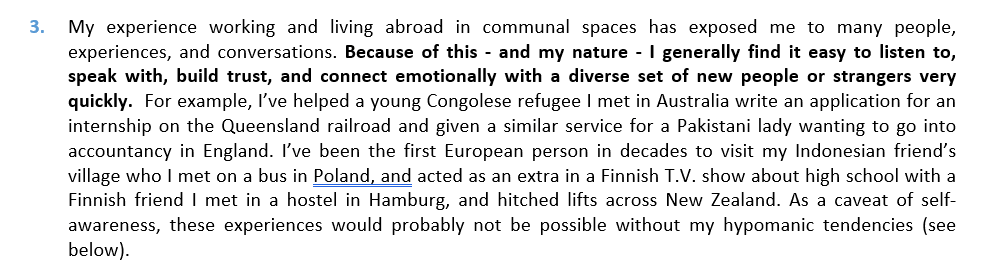

It may even come in useful for your career. I recently started training to become a Children's Emotional and Behavioural Psychologist, and the employers identified a key skill was 'being able to quickly build relationships with people'.

See below from an extract from my job application:

Again, such experiences may come across as bragging.

As in, this guy:

But the more fundamental point is that such experiences do not happen to special people: they happen to people who place economic scarcity upon themselves to create demand, who go solo travelling, and who then reciprocate with others.

Again, the conditions you will find out there are set up so that connection with others is easy; the rest merely follows from friendship.

Solo travel cannot be planned to happen in the way this post has described, though you should do your research about the likelihood of being able to do things like finding a place to live and work.

Berlin, for example, had a hostel that supported long term living for 100 Euros a week, and I knew it had many Irish pubs, which would likely recruit English speakers - even if I couldn't speak German (which I couldn't).

Remember, scarcity creates demand, and that you have choices, and great chances at connection, though never guarantees.

Conclusion

Economics is about the real world, and how it really works. I suggest further that you cannot learn about personal economic demand from a book, or a blog post, you must experience it for yourself.

There is nothing guaranteed, magical, or perfect about solo travel. When you go, you should expect to be lonely, scared, and unsure.

But know that scarcity creates demand. Go to hostels. Ask questions. Speak to people. Find local work. Make an effort to reciprocate with others.

And one day you may just look back and think it was one of the best times of your life. The everyday life of routine cannot compare to one with so many different economic demands placed upon you, in so many different ways.

And who knows, you may surprise yourself. I know I did.

Positive reason #1: Create personal economic demand.

References

1) Sowell's Basic economics (2000)

2) Maslin's How to save our planet (2020)

3) Nutt's Drugs without the hot air (2018)

4) Pinker's Enlightenment now (2018)

5) Taleb's Antifragile (2012)